“TThe narrator’s voice snaps you up,” reads The New York Times review of The Committed, by Viet Thanh Nguyen. “It’s direct, vain, cranky and slashing—a voice of outraged intelligence. It’s among the more memorable in recent American literature.”

This year’s seventh annual Amherst Litfest also snapped up, to use the Times’ phrase, Nguyen and other powerful writers, bringing them to a campus gone snow-bright after a recent blizzard. The guests included Pulitzer Prize winner Natalie Diaz; Katie Kitamura and Elizabeth McCracken, who were longlisted for 2021 National Book Awards; journalists Vann Newkirk and David Graham; and more.

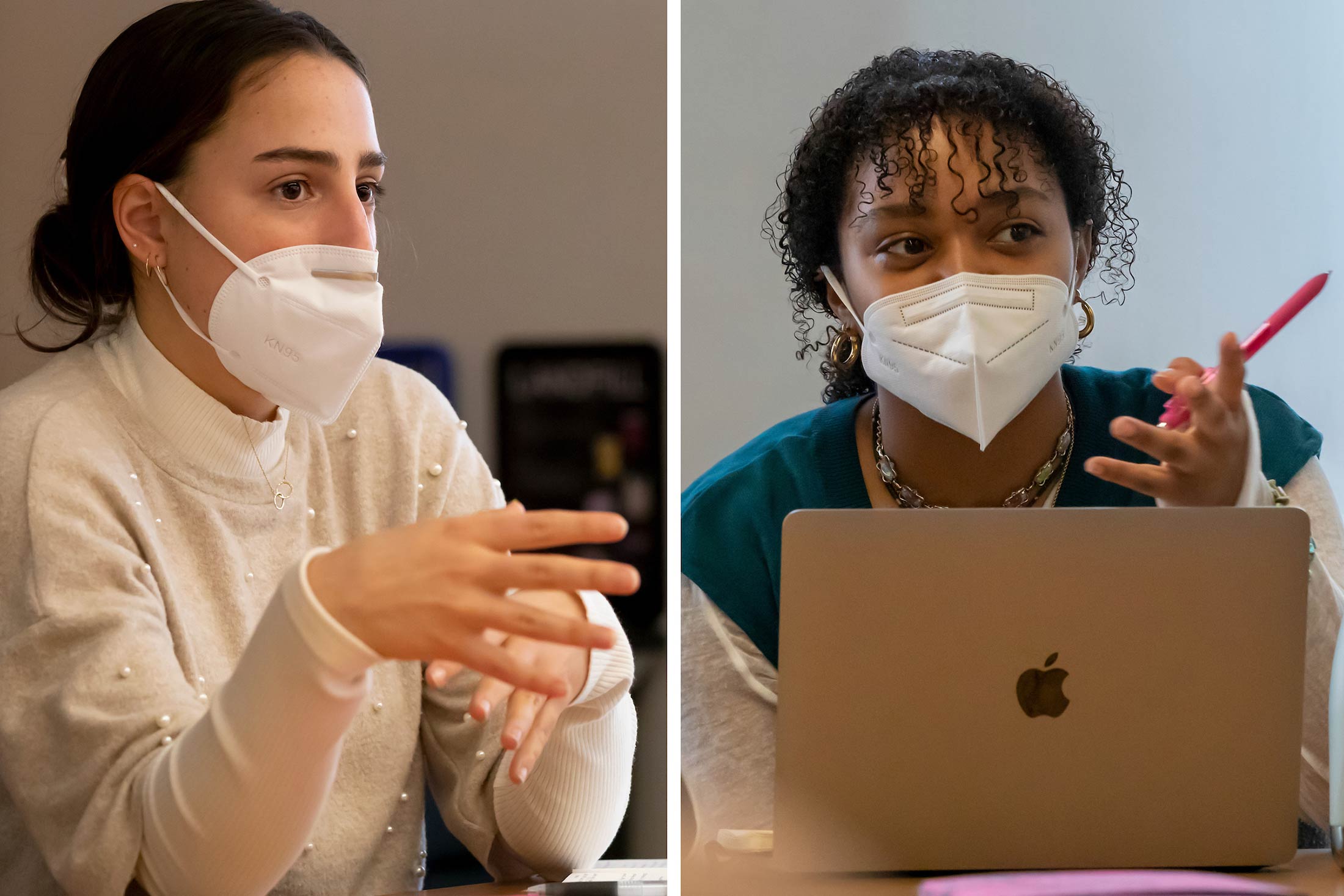

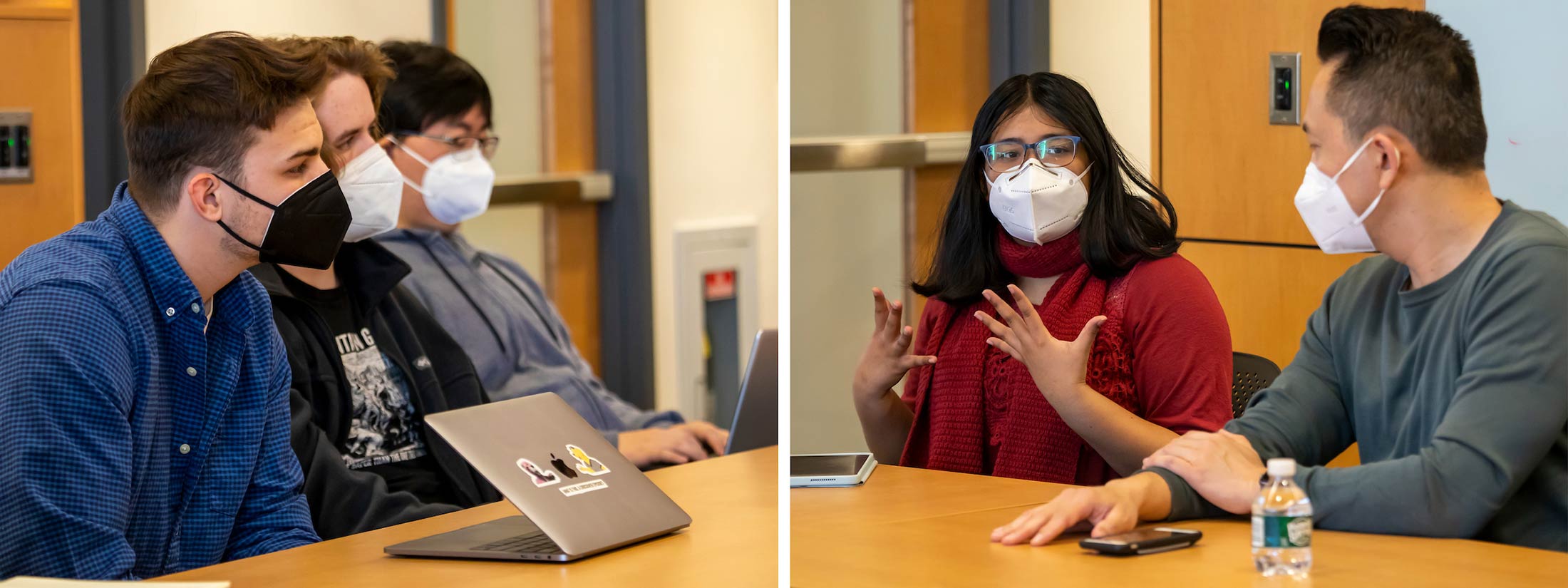

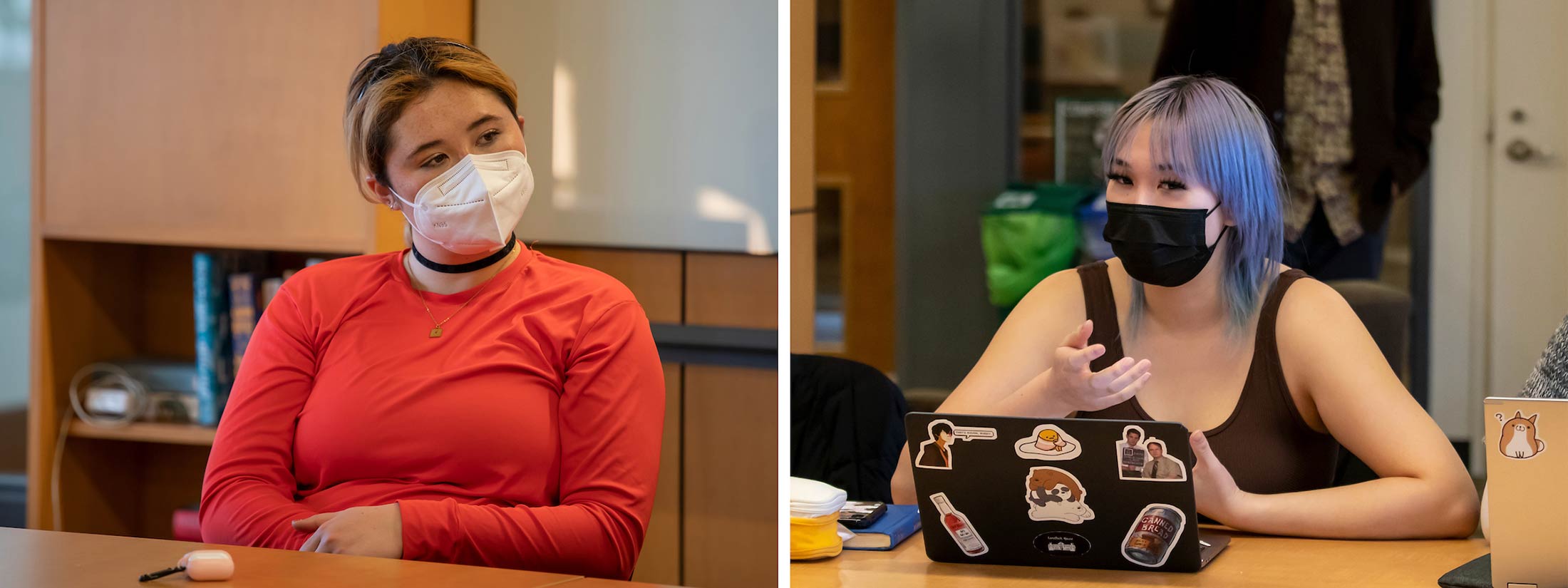

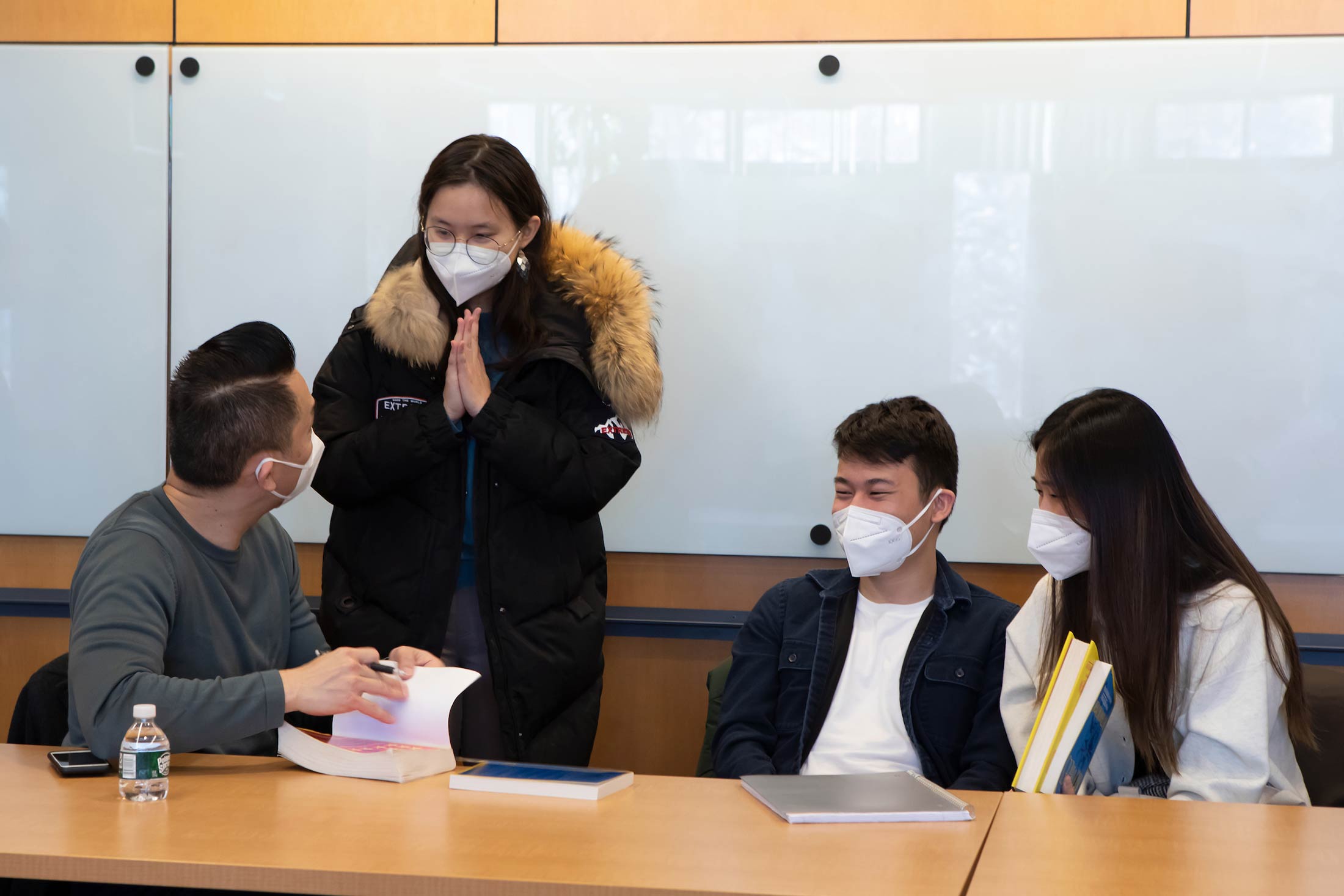

From Feb. 24 to 27, the writers engaged with the campus community, speaking at Johnson Chapel, sitting in on classes and sharing their insights. The four novelists also plunged into close colloquy with students by giving “craft talks” on how they craft their narratives—while coaching students on how to make their own stories come alive. We covered two such talks, one offered by Nguyen (who slashed at the idea of “craft” altogether) and one by Kitamura, who had Amherst students probe current events for inspiration.

Just a Writer. “I don’t do craft.” That’s the first thing Viet Thanh Nguyen declared to the 20-plus students gathered at Frost Library for his craft talk. Nguyen elaborated: Learning the craft, the techniques of fiction writing—narrative, plot, point of view, etc.—doesn’t necessarily teach you anything about how to write about ideas and personal passions related to race or politics, or, in Nguyen’s case, his own family history of being a Vietnam War refugee. “I also don’t call myself a creative writer,” Nguyen continued. “It seems kind of redundant. Why do you have to be a creative writer? If you’re a writer, you should be creative.”

The House of No Books. Students listened closely as Nguyen shares that he was raised in a religious home that was void of books, not even a Bible. Ngyuen forged his love for literature at the San José, Calif., public library. This passion led him to UC Berkeley, where he discovered books beyond the classic, literary canon, venturing into Asian American literature, African American literature and post-colonial literature. He also took a writing class taught by Maxine Hong Kingston, author of The Woman Warrior. There, Nguyen began to grapple with the non-technical issues of writing, issues related to implicit bias, representation and translation. How, he wondered, can he keep his own implicit biases out of his fiction writing?

The Burden of Representation. Nguyen touched on issues of audience and translation. Writers who are “normatively identified in whatever way, whether it’s their race or their class or their gender, don’t get asked or really have to think about who they are writing for,” he told the students. Such writers can assume that their audience will understand their references and their culture, and so they don’t have to define or explain what’s going on. Nguyen’s advice? Don’t try to humanize your characters. They’re already human.

The Spreadsheet. Nguyen spoke about the 17 years he spent writing The Refugees (yes, 17 years; more about persistence in a minute), and the massive Excel spreadsheet he created for its themes, characters, events and perspectives. This effort allowed him to deliberately develop a diverse set of situations and characters—young, old, gay, straight, male, female, Black, white, Asian— without slipping into representing or defining any one identity through a single lens or character. When asked how writers can heal from what they don’t know about their own personal history, Nguyen paused: “Wow. If I could answer that question, I’d never be out of business.” After the laughter subsided, he continued: “I don’t think of writing as a form of healing. I think of writing as a form of grieving, of mourning.” Individual grief doesn’t allow a culture to heal, he added. “Literature can show the possibility of healing, but it can’t heal. … Literature can’t change anything. Action can change things.” One student asked how he approaches writing from another identity. In response, he invoked author Alicia Elliot and fellow Litfest author Natalie Diaz. “Empathy is not enough,” said Nguyen. “Instead, you need to write with love.”

What Craft Doesn’t Teach You. At the end of the session, many students stuck around for autographs. “None of my writing workshops ever taught how to write about history or theory or politics, or philosophy,” Nguyen told them. “I never understood why that was the case. Why is a writing workshop only devoted to craft, and why is craft only about … technical issues?” Early in his career, he didn’t consider himself to be a good writer. But was extremely stubborn. The only thing that makes you a good writer is to read and write a lot, he insists. “If you have to choose,” he said, “between talent and persistence, take persistence.”