In the days after the death of Robert Brustein ’47, the influential stage director and theater critic, I reread a piece he wrote in the ’60s that is part of his book The Third Theatre (1969). In it, he discusses a fringe artistic movement, what he called “a new theater” evolving in opposition to Broadway. This, in his view, was reason to rejoice. However, as it evolved he watched in dismay as the movement captured the bulwarks of theatrical power, becoming part of the mainstream. It’s worth quoting him at length:

This development closely paralleled a failure of nerve among the middle class, as the forces of the establishment grew guilty and enfeebled before the culture of the young, and the American avant-garde, for the first time in its history, became the glass of fashion and the mold of form. What was once considered special and arcane—the exclusive concern of an alienated, argumentative, intensely serious elite—was now open to easy access through television and the popular magazines; vogues in women’s fashions followed hard upon, and sometimes even influenced, vogues in modern painting; underground movies became box office bonanzas, and Andy Warhol’s Factory was making him a millionaire.

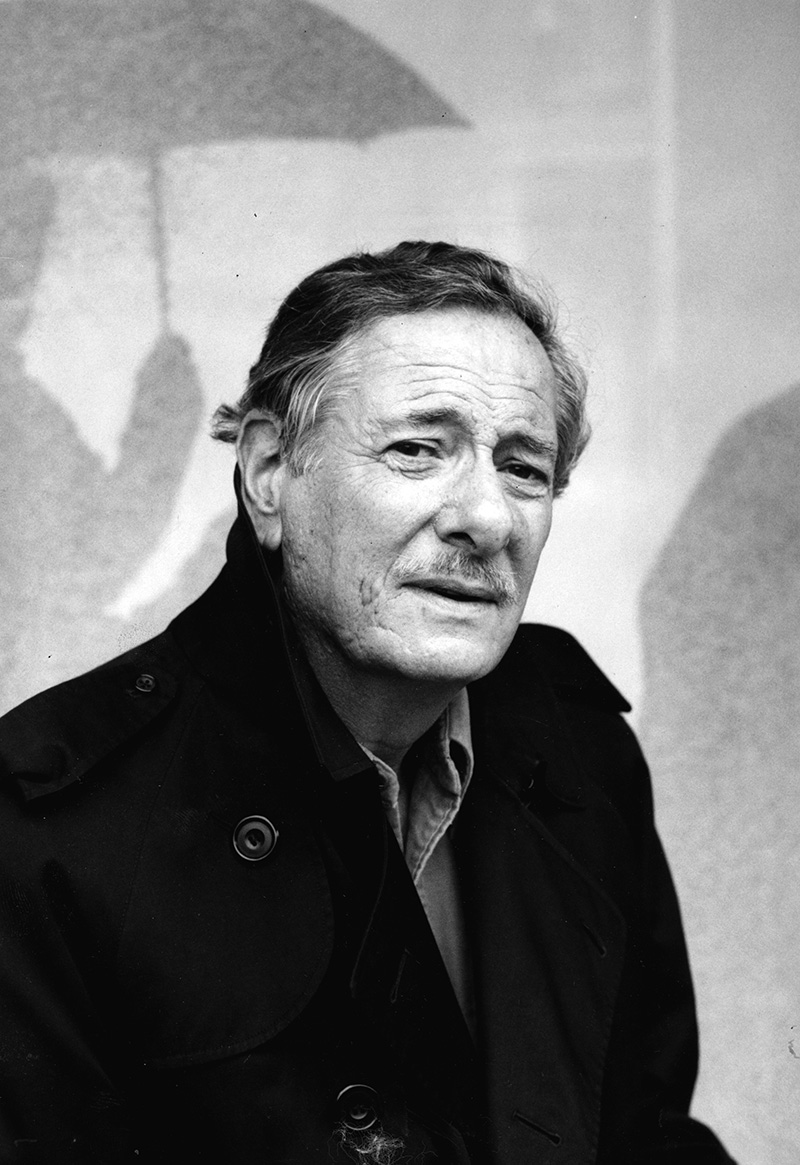

I support not only what Brustein says but the courage he displays in saying it. Rereading the essay also made me appreciate the degree to which he had shaped my voice in the public debates I have had over the last decades. He died on Oct. 29, 2023, at the age of 96. I never met him in person. In the late 1990s, when I spent parts of the summer in Martha’s Vineyard, where Brustein had a beach house, I would often think of introducing myself. I never saw any of his adaptations of Chekhov, Ibsen, Strindberg or Pirandello, in part because, at the time they were performed, I was a broke young man. But I admire his determination to adapt these stage titans, as if saying that at times you need something more than a translation. You need an adaptation in order to make the classics speak to new audiences.

What I was, consistently, was an assiduous reader of Brustein’s columns, in The New Republic and elsewhere. Even when I would utterly disagree with him, I found these works admirable. When I recall the feeling I would have after finishing any of them, I sense a dialogue across generations. It was as if he and I had met frequently for coffee, just to exchange opinions.

Therein, indeed, was the most valuable lesson I learned early on from the author of Letters to a Young Actor (2005) and other books: In a democracy, it is crucial to speak one’s mind, to do so with flair and aplomb and, most importantly, to offer as wholesome a context for one’s argument as possible. In The Third Theatre, Brustein emphasizes that we depend on the young for renewal. Without them, he says, there is no future. Yet he also cautions the young about complacency, about an insatiable desire for fame at the expense of uniqueness. It is important for the young to know the pitfalls their predecessors have fallen into and to be conscious of the traps set for them in our culture of narcissism.

The New York Times called Brustein a “contentious advocate for profit-indifferent theater.”

Of course, in the age of social media, everyone has access to a microphone. The loudest and most outrageous get the most attention. Success is measured by the number of followers. There is the constant fear that if you say something wrong, against the herd, you will be censored, meaning you will have a battalion of enemies. This is a mirage: To speak up isn’t the same as speaking out.

Often after writing for The New York Times, as I did recently about the survivalist instincts of Yiddish, or for Time about the history of the exclamation mark, or about the elasticity of the English language for The Wall Street Journal, or while reflecting on a variety of topics in an NPR show, I get a barrage of reactions in the thousands. They range from laudatory to menacing, including death threats.

I have learned the value of having an antagonist, someone whose outlook is regularly testing mine.

Although no one enjoys such aftermath in a civil conversation, I have learned that it comes with the territory. In fact, it is best not to respond to them head-on, since, for the most part, this is impulsive feedback by an audience eager to let you know what’s on its mind. What is central is not to allow this effervescence to intimidate you. While democracy is by definition a cacophonous system of governance, as long as it works it isn’t chaotic.

In academia, we are afraid of negative reviews. Yet negative rejoinders are as important to building consensus as benign, adulatory approvals. The real world is cruel. For as much as we manifest it, gentility isn’t a sine qua non. Furthermore, I have learned over the years the value of having an antagonist, someone whose outlook is regularly testing mine and vice versa.

I’m convinced that the measure of one’s talent depends on the qualifications of our antagonists: The more adept, insightful and conscientious our opponents are, the better our own arguments are likely to be. Notice I didn’t use the word enemy. An antagonist is different from an enemy, at least in my personal dictionary. The former is about an unlikely partnership, whereas the latter is about destruction.

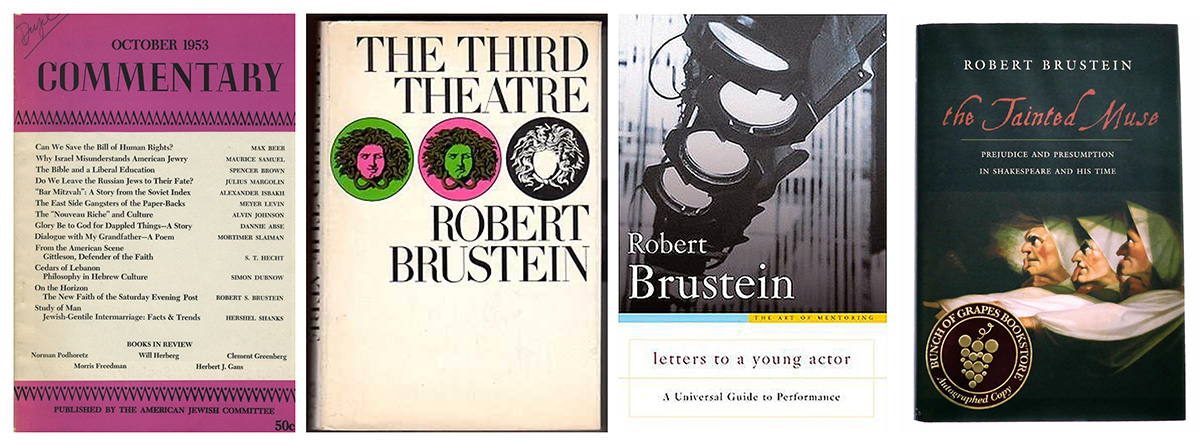

First: 1950s–2010s, Brustein wrote criticism for many magazines, including Commentary; second: 1969, The Third Theatre appraised the decade’s trend toward fringe theater; third: 2005, Letters to a Young Actor recounts Brustein’s advice to actors such as Meryl Streep; fourth: 2009, The Tainted Muse explores elitism, racism and misogyny in Shakespeare.

At Amherst, Brustein wanted to be a medievalist. After he graduated, he nurtured the vision of becoming a scholar. But he couldn’t imagine getting a job far from the epicenters of art. Slowly, he began to contribute to magazines like Commentary. Theater was his passion. He wasn’t an actor. Instead, what he loved was how a play might, to cite Hamlet, “hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature.”

Where I was growing up, I too wanted to be in the theater. My father was a telenovela star; yet where he felt fulfilled was onstage. At Sunday matinees, I would sit behind the curtains while he performed, looking at people hypnotized by his gesticulations, his pantomimic movements, while I, in contrast, would be mesmerized by the metamorphosis he had undergone, from being my father to becoming a hospital nurse, a cabaret singer or a concentration camp prisoner. There was magic in him and other actors escaping their own condition, becoming someone altogether different for two hours or so.

I had a forgettable cameo in one of my father’s soap operas: I was a patron at a bar where he was the maître d’. In the film My Mexican Shivah, based on a short story of mine, I was supposed to come out of an elevator with my father into the Mexico City apartment where most of the action takes place, but the scene was cut out at the last minute. And I also directed plays—one of them, Yentl, by Isaac Bashevis Singer, with my father. My heroes were directors such as Jerzy Grotowski, Tadeusz Kantor and Peter Brook. Over the years, I have written for the theater and have performed in it, including a solo show called The Oven, about religious reawakening at a time of crisis.

I opted at some point for literature, because I enjoy the experience of imagining an alternate universe on my own, and I value the written word as a tool for change. Upon arriving in New York as an immigrant, I began hearing about Brustein. The fact that he committed himself fully and unreservedly to theater as a forum of democratic exploration enthralled me. That’s what the arts are for: Rather than being subversive for sheer shock value, their function is to examine the boundaries of our consciousness and to bring audiences into close proximity to those unlike us.

In one of Brustein’s most notable polemics, which took place in 1990, he challenged August Wilson—the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright whose Pittsburgh Cycle, including Joe Turner’s Come and Gone and Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, redefined the 20th-century American stage—about who should direct his plays. Wilson wanted only Black directors to do the job. Brustein disagreed. For him, this was a betrayal of the essential idea that theater is an art where we go beyond our individual boundaries. Indeed, he saw it as another form of ghettoization. He believed Shakespeare and others, onstage, have no color.

That is why, I believe, plays such as Macbeth and King Lear ought to be performed by actors of every background. Visualizing rotating versions of Romeo and Juliet, set among Palestinians and Israelis, with alternative directors from either side, keeps Shakespeare fresh. When produced wisely, these versions not only allow us to once again celebrate Shakespeare’s audacity; they also invite us to be appreciative of the whole gamut of human personalities.

I agree with Brustein. His argument must be expanded beyond theater—into the classroom, for example. It would be stifling to have students learn about Mexican literature exclusively from Mexican teachers. Having among the teachers someone from a different background enriches the overall experience. For instance, as a Jew I deeply cherish the dialogue I sustained in the early ’90s with Palestinian American scholar Edward Said, author of Orientalism, on New York’s Upper West Side. Because, in the end, pluralism is the capacity of individuals to coexist with one another, not in their own silos but by building bridges. To remain solid, those bridges depend on the empathy of those who are unlike us.

First: 1947, Brustein’s Olio photo. His activities at Amherst included fencing, Masquers and baseball; second: 1984, Brustein directed Samuel Beckett’s Endgame; third: 1990, Brustein publicly argued with playwright August Wilson.

Another one of Brustein’s pugilistic matches, mentioned in his New York Times obituary, involved Samuel Beckett. In 1984, before the premiere of his 1957 play Endgame at the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Mass., Beckett complained that Brustein’s stage version took many liberties, including the casting of Black actors, and tried to stop the production in its tracks. Brustein argued—wisely, in my opinion—that a playwright’s stage directions are merely suggestions. For theater to be a forum of experimentation, the actors, director, stage designer and others involved must be free to interpret the material as they see fit.

The two sides negotiated an agreement whereby the production’s program would include a statement from Beckett: “My play requires an empty room and two small windows. The American Repertory Theater production which dismisses my directions is a complete parody of the play as conceived by me.” And while he never saw a rehearsal, let alone the production, Beckett added, “Anybody who cares for the work couldn’t fail to be disgusted by this.” Mercifully, the program featured Brustein’s response as well: “To threaten any deviations from a purist rendering of this or any other play—to insist on strict adherence to each parenthesis of the published text—not only robs collaborating artists of their interpretive freedom but threatens to turn the theater into a waxworks.”

Bravo, Brustein! If we adapt Shakespeare to our needs every time we stage it, why not do it with contemporary playwrights as well? The moment authors—playwrights and others—make their work public, it no longer belongs to them alone. Needless to say, they should receive revenue for the duration of the copyright. The beauty of art is that it is enhanced through the eye of the beholder. Not only are two performances of the same play different from one another; a stage version is never the original, nor is it like other versions. In art, the interpreter is a co-author.

In fact, one of Brustein’s most significant messages, one I have turned into my mantra, is that purity in art is impossible. Shortly after his death in 1616, Shakespeare went through a period of eclipse. It wasn’t until the 18th century that he was “revived,” starting his journey into the object of jealous adoration he has been turned into. When first staged, his plays were performed with almost no props. Successive interpretations added every type of extemporaneous artifact imaginable: bollock daggers, velvet curtains and Jacobean furniture. Authenticity, obviously, comes at a price, including the joy of anachronism.

In the program, Brustein and Beckett aired their vehement disagreement on how Endgame should be staged.

In The Third Theatre, Brustein asks: “Is there something in the American character that pushes our culture toward extremes?” It is a wonderfully prescient question. It the United States, we like to say that we want to find the middle ground, but we don’t always end up there. Polarization gets accentuated during certain periods. Like now, when it feels as if the national character has gone rogue, coming close to breaking into smithereens. The fear of violence is in the air. Anxiety is a normal reaction.

The answer is not to shy away from dialogue, especially when it is with people who, on the surface, are on the opposing side. Actually, it is with that side where we need the tête-à-tête most. If democracy is to endure, its fractures adequately addressed, it is with the arts as a tool for investigation, not simply provocation. The arts that are youthful, yet mature.

Brustein is right: In order for the young to comprehend the challenges they face, they must understand how history works in all its intricacies. Equally important, they must be tolerant of dissent and even ready to engage those they viscerally repudiate. I’ve been a teacher long enough—30 years at Amherst alone—to know how difficult this is today. The young generation wants to be coddled; it doesn’t like departing from its comfort zone. Universities cater to those emotions. They see students as delicate, in need of protection.

Education is measured by the capacity to have an individual viewpoint and to see reality through another set of eyes. I don’t know what Shakespeare thought of Iago or Lady Macbeth. I hope he was appalled by their actions. But it is unquestionable that, as characters, he shaped them admirably, even reverentially, as he did all his other creations.

I write these words because, now that Brustein is gone, I miss him dearly. He was fizzy and spirited and, most of all, independent. It is a quality I cherish above all others.

Ilan Stavans is the Lewis-Sebring Professor of Humanities and Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College, the publisher of Restless Books and a consultant to the Oxford English Dictionary. University of Toronto Press just released a collection of his essays and interviews titled Translation as Home: A Multilingual Life, edited by Regina Galasso.

Photograph by Janet Knott / The Boston Globe / Getty Images

Endgame photo: American Repertory Theater / Richard Feldman; Brustein photo: William Sauro / The New York Times / Redux