In the fall of 2023, the Emily Dickinson Museum’s new database came online. This exhaustive collection could be described, in the words of the poet, as an “Enormous Pearl” (Fr524) in both scope and caliber. The 8,300-plus artifacts from the family’s two homes, the Homestead and the Evergreens (the latter of which just reopened to the public, post-renovation, in March), remained largely unstudied and inaccessible until 2019. That’s when a major grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services supplied funding for the cataloging of the collection.

Among the artifacts are fine art, including an impressive array of Hudson River School paintings; kitchen, dining, lighting and heating wares; personal items, such as Edward Dickinson’s wallet and Susan Huntington Gilbert Dickinson’s sewing kit; musical instruments; children’s toys; handwork; a large assortment of clothing; and souvenirs from travels abroad.

As Emily Dickinson so wisely put it, “The Object Absolute - is nought - / Perception sets it fair” (Fr1103). Indeed, this collection of objects offers a close and vivid view of a family living in a semi-rural 19th-century community and the daily life and writing habits of one of the world’s greatest poets. You can search the database at EmilyDickinsonMuseum.CatalogAccess.com. But, for now, enjoy this selection of some of the most charismatic items—and the poetry they conjure.

Blue Staffordshire Teapot

This transfer-printed pearlware features a dark blue enamel underglaze. On the bottom of the teapot is embossed “Adams Warranted Staffordshire.” As treasurer of Amherst College for 37 years, Edward Dickinson hosted the annual Trustee Commencement Tea at the Homestead. At one such event, Emily, his daughter, was spotted in the dining room pouring not tea but sherry, while deep in conversation with one of the dignitaries.

From “Sic Transit Gloria Mundi” (“Thus Passes the Worldly Glory”), Emily’s first published poem (Fr2):

Peter, put up the sunshine;

Patti, arrange the stars;

Tell Luna, tea is waiting,

And call your brother Mars!

Ned’s Banjo

This five-string banjo has a natural vellum head and metal tailpiece and brackets. The instrument's style and manufacturer’s name (“Artist Banjo, Thompson & Odell”) is stamped on the bottom side of the dowel stick. The underside of the drumhead is initialed in pencil. Thompson & Odell was a Boston music publishing company that also sold and repaired instruments. The banjo was presumably owned by Emily’s nephew Ned. Banjo and mandolin clubs appeared at colleges around the country in the 1880s. Ned Dickinson (class of 1884) belonged to the Amherst College Banjo Club, and Dickinson family sheet music includes banjo pieces. Such clubs were not reserved for men alone; Ned’s sister, Martha, also played the banjo and reported on a summer banjo-themed excursion to Ashfield, Mass. Emily wrote of music (in Fr1511):

The fascinating chill that Music leaves

Is Earth’s corroboration

Of Ecstasy’s impediment -

’Tis Rapture’s germination

In timid and tumultuous soil

A fine - estranging creature -

To something upper wooing us

But not to our Creator –

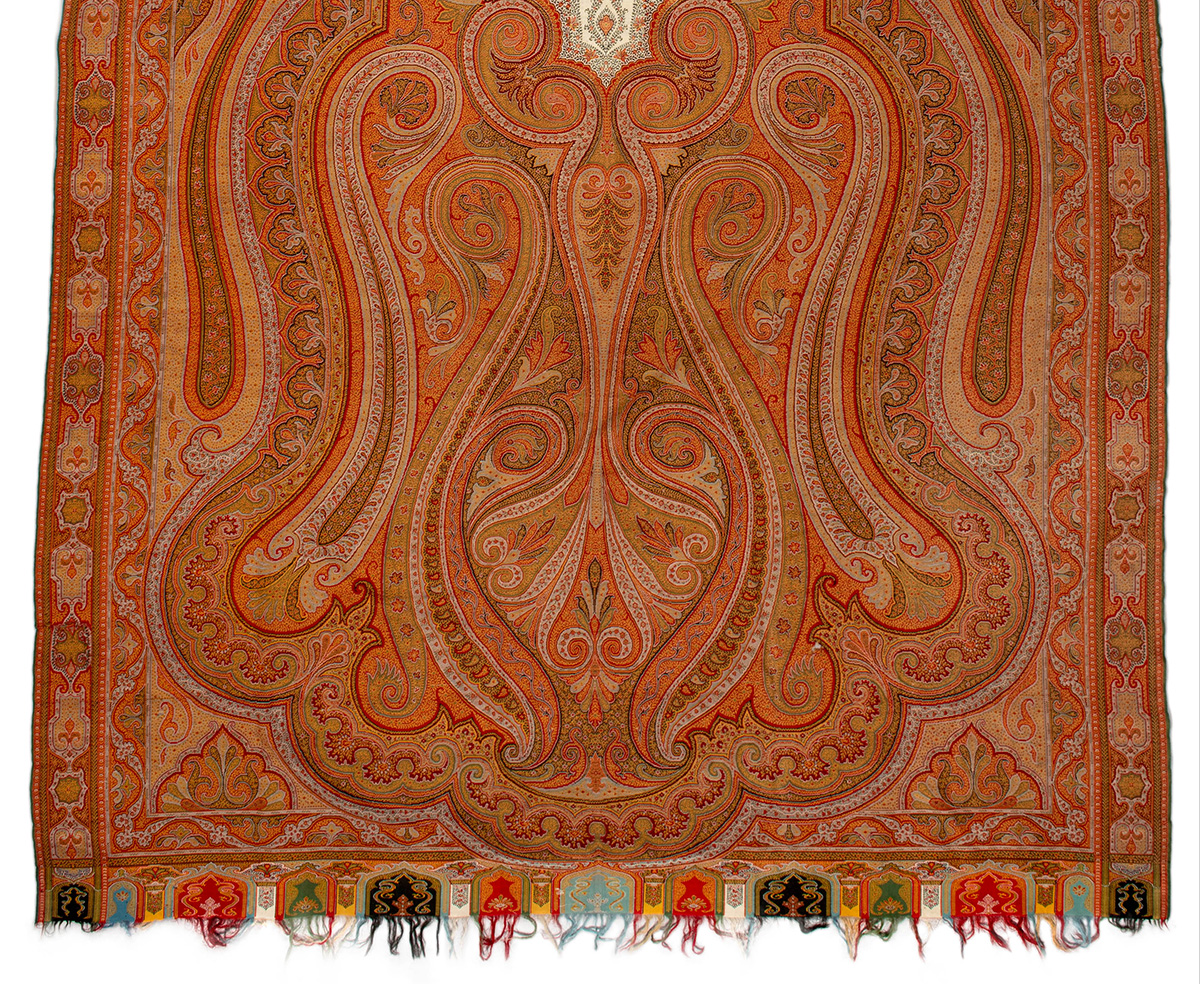

Emily’s Shawl

This sprawling, rectangular woven shawl is associated with Emily Dickinson. (See an excerpt from Fr522 below.) The paisley design is mainly red, orange and light blue with other minor colors throughout. All four sides display a border design, with the shorter sides ending in fringe. The cloth features a large, symmetrical pattern in the main body with a white cotton or linen section in the center. Popularly known as “India shawls,” many of these were actually manufactured in England and France.

I tie my Hat - I crease my Shawl -

Life’s little duties do - precisely -

As the very least

Were infinite - to me –

A Photograph of Susan Huntington Gilbert Dickinson

This daguerreotype is held in an ornate wooden case, with an interior of faded purple velvet embossed with a symmetrical paisley design. The image dates from 1856, the year Susan married Emily Dickinson’s brother, Austin. The venue of their July 1 wedding was abruptly changed from Amherst to the home of Susan’s aunt in Geneva, N.Y. No other Dickinson family members were present. Emily’s 36-year friendship with Susan was one of the most intimate and fascinating of her life. She wrote hundreds of letters to Susan over the years, including the following poem (Fr1658):

Show me Eternity, and I will show you Memory -

Both in one package lain

And lifted back again -

Be Sue, while I am Emily -

Be next, what you have ever been, Infinity –

Susan’s Needlepoint

This fireplace screen, with a wooden pole and needlepoint pattern under glass, is the handiwork of Susan Dickinson, Emily’s sister-in-law. It depicts a basket of flowers (dahlias, morning glories, lily of the valley and more) crafted with wool thread on linen ground inside a square frame. The carved pedestal base has three legs with scroll feet. The museum’s collection also holds the original pattern, produced by Carl F.W. Wicht of Berlin. Wicht was a major producer of embroidery patterns, each printed on a finely ruled grid with recommended colorways added by hand. These cross-stitch patterns were often worked in high-quality Berlin wool and remained popular for much of the 19th century. Susan may have acquired this pattern in her young adulthood, since the Wicht company ceased production in 1858. Practical as well as decorative, Susan’s framed needlework, mounted on a pole screen, would have been adjusted to block excessive heat from the fireplace. Wrote Emily (in Fr681):

Dont put up my Thread & Needle -

I’ll begin to Sow

When the Birds begin to whistle -

Better stitches - so -

Ned’s Toy Steam Engine and Edward’s Wallet

This toy steam engine train is made of wood overlaid with chromolithograph (colored printing) decorations in green, gold and red. A metal bell is fixed near the smokestack. There are eight wooden wheels, with the back two connected by an axle, plus an open wooden coal house and a gold-painted “Hercules” on the side. Can you spot the engineer in the window?

Stamped in gold foil on the front of this black leather wallet is “Edward Dickinson,” the name of Emily’s father. The wallet features an envelope-style front flap and metal clasp, with a blue leather interior and royal blue fabric lining the pockets. The inside front flap has a pocket for “Postage” and a pocket for “Tickets.” There is also a place to store a writing utensil.

Edward Dickinson was largely responsible for securing train service to Amherst in 1853. Emily wrote that, at a celebration of the event, her father “went marching around … like some old Roman General, upon a Triumph Day.” Understandably, his grandchildren also adored toy trains. On a morning visit to The Evergreens, the stern “straight engine” Edward Dickinson earned a sharp reprimand from one of these children playing with a toy train: “Get out of the way there, Mister G’andpa!” Charmed by the outburst, Edward took out his wallet and rewarded the young engineer with 25 cents. And Emily marveled at the journey of a train (Fr383):

I like to see it lap the Miles -

And lick the Valleys up -

And stop to feed itself at Tanks -

And then - prodigious step

Around a Pile of Mountains -

And supercilious peer

In Shanties - by the sides of Roads -

And then a Quarry pare

Jane Wald is the Jane and Robert Keiter Family Executive Director of the Emily Dickinson Museum. Megan Ramsey is the museum’s collections manager, and Patrick Fecher is associate director of communications. For more information, visit EmilyDickinsonMuseum.org. Madeline Levine is communications coordinator in Amherst College’s Office of Communications.