An Even Better Home at Amherst

By Daria D’Arienzo and Margaret R. Dakin

Though she has been dead for more than 120 years, people still dream of receiving a letter from Emily Dickinson. In December 2006, three of the poet’s letters arrived at the Archives and Special Collections in the Amherst College Library.

Daguerreotype image of Emily Dickinson by William C. North, daguerreotypist. |

Through the generosity of Thomas Michie, three notes—including two poems—and one envelope that started their journey here in Amherst and stayed a long while in Worcester, Mass., have now returned home to Amherst.1 These notes are from Emily Dickinson to one of Michie’s ancestors, Sarah Tuckerman, who was the poet’s neighbor and the wife of an Amherst professor.

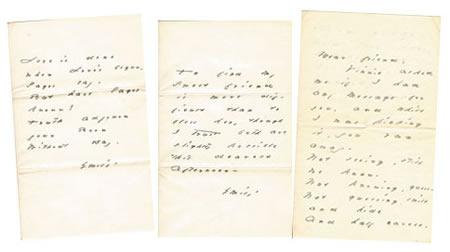

Left: “Love is done/when Love’s begun,” circa 1880. Center: “To find my sweet friend is more difficult than to bless her,” Sept. 6, 1881. Right: “Vinnie asked me if I had any message for you,” December 1881. |

The letters date from the 1880s, by which time Dickinson was not leaving her father’s house, known in those days as “The Mansion.” Dickinson’s notes and tokens were her social intercourse. The poet regularly sent notes to many friends and family members, even those who lived in town. Written in the later years of Dickinson’s life (she died in 1886), the Michie manuscripts illustrate the last phase in the evolution of the poet’s handwriting from a schoolgirl’s script to a more open, “postmodern” cursive interpretation of printed letters.

The first leg of the new manuscripts’ journey ended just across town from Dickinson’s home on Main Street in Amherst, at the South Pleasant Street home of the Tuckermans.

The earliest manuscript, a poem from late 1880, is “Love is done/when Love’s begun”:

Love is done

when Love’s begun,

Sages say –

But have Sages

known?

Truth adjourn

your Boon

Without Day.

Emily.3

The second manuscript is a note from Dickinson to “Mrs. Edward Tuckerman” dated “6 September 1881” and written in Dickinson’s distinct hand. She signed it “Emily.” Dickinson sent the letter on the day that Frederick Tuckerman, the nephew who made his home with Sarah and Edward, married Alice Girdler Cooper.4 Referring to the day’s significance, the poet wrote:

To find my sweet friend is more difficult than to bless her, though I trust both are slightly possible this dearest Afternoon–

Emily.

The third manuscript is a note that contains the poem “Not seeing, still we know–.” Apparently inspired by the poet’s sister, Lavinia, the note dates from December 1881:

“Mrs. Prof Tuckerman,” Nov. 8, 1881.

Dear friend,

Vinnie asked me if I had any message for you, and while I was picking it, you ran away.

Not seeing, still

we know –

Not knowing, guess –

Not guessing, smile

and hide

And half caress –

And quake –

and turn away,

Seraphic fear –

Is Eden’s

innuendo

“If you dare”?

Again, she signed it simply “Emily.”

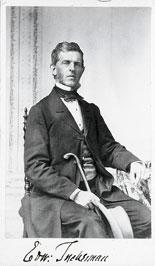

Professor Edward Tuckerman, circa 1863. |

A small envelope addressed in Emily’s distinctive late-life hand to “Mrs. Prof Tuckerman / Amherst–” constitutes the fourth manuscript. (Dickinson did not always address her envelopes, often enlisting others to do so on her behalf.) This envelope bears a postmark of “Nov 8” and is docketed in an unknown hand with “Emilie Dickinsin” [sic] and “8th Nov. 81.” In yet another unidentified hand, the envelope is additionally annotated: “The dandelion’s pallid tube,” indicating that the envelope originally enclosed the only known copy of that poem, now at the American Antiquarian Society.5

In his three-volume Letters of Emily Dickinson, Thomas Johnson lists 28 surviving pieces of correspondence from Dickinson to Sarah Tuckerman. Two of the recently donated Michie manuscripts (“To find my sweet friend” and “Dear friend, Vinnie asked me…”) are among them, and the envelope belongs to yet another manuscript in the list (“The dandelion’s pallid tube”). The poem “Love is done when Love’s begun” is not included in Johnson’s list of correspondence because there is no note along with the poem (although one suspects there might have been one originally). The poem is included in both Johnson’s and Franklin’s editions of the collected poems.

The Tuckerman house on South Pleasant Street, circa 1890. Note the Tuckerman monogram on the stone set over the front entrance. Below is the interior.  |

Dickinson’s earliest known correspondence to the Tuckermans (published first in the 1894 edition of Todd’s Letters) is from 1874, the date apparently having been noted by Sarah Tuckerman herself.6 A diary that Sarah and Edward Tuckerman kept jointly between mid-January and early April 1860 indicates that there was earlier correspondence (though the earlier letters are not known to have survived).7 Sarah Tuckerman noted in the diary that on Friday, Jan. 20, 1860, “Miss Lavinia Dickinson came with a note & two flowers from her sister.” On Jan. 30, Sarah wrote that she returned the visit: “After dinner S.E.S.T. [Sarah Eliza Sigourney Tuckerman] called at Miss Allen’s and on Mrs. Ed. Dickinson and daughters. Saw Miss Lavinia.” In fact, during the short time the diary covers—some 78 days in the middle of a New England winter—the Tuckermans recorded three visits to or from members of the Dickinson family, including one from Lavinia and Emily herself on a cold Saturday, Feb. 11, 1860.8 Sarah wrote: “Saturday 11th Feb. Chilly day. S.E.S.T. did not go out all day. E.T. [Edward Tuckerman] walked ‘round the square.’ Misses Emily and Lavinia Dickinson called this afternoon.”

Members of the Cushing family, May 1, 1848. From left: Anna Louisa Cushing (1834-1923); Sarah (Wayland) Cushing (married 1843, died 1875), Thomas Parkman Cushing’s third wife and the sister of Francis Wayland, president of Brown University; Andrew John Cathcart Sigourney (1824-1869), Sarah Cushing’s stepson from her second marriage; Thomas Parkman Cushing (1787-1854); Sarah Cushing (1832-1915); and Martha Ann Cushing (1837-1887) Members of the Cushing family, May 1, 1848. From left: Anna Louisa Cushing (1834-1923); Sarah (Wayland) Cushing (married 1843, died 1875), Thomas Parkman Cushing’s third wife and the sister of Francis Wayland, president of Brown University; Andrew John Cathcart Sigourney (1824-1869), Sarah Cushing’s stepson from her second marriage; Thomas Parkman Cushing (1787-1854); Sarah Cushing (1832-1915); and Martha Ann Cushing (1837-1887)Photo courtey of Thomas Michie. |

In their day, the Dickinsons and Tuckermans were among the most prominent town families. Their relationship seems to have been one of warmth and endurance. Because of the poet Emily, the Dickinsons are well known today; the Tuckermans less so (although Tuckerman’s Ravine in New Hampshire’s White Mountains bears the family name). Who, then, are the Tuckermans?

The Dickinsons and Tuckermans were both linked to the town of Amherst and to the college, as well as to each other through their social standing and friendship. The extended Tuckerman family has multiple connections with the college, including through the Esty family. It is likely that several generations of Tuckermans and Estys knew members of the Dickinson family throughout the years.9

Edward Tuckerman provides the first link. Professor Tuckerman was an established authority on lichens and a professor of botany (among other things) at the college from 1854 to 1886. On May 17, 1854, he married Sarah Cushing, 15 years his junior and the daughter of his father’s business partner, Thomas P. Cushing of Boston. The Tuckermans lived about a mile from the Dickinsons in a “substantial residence on South Pleasant Street” where Amherst College’s Coolidge Cage now stands.10 Edward was a serious, committed scientist and scholar—with perhaps something of a melancholy strain—who suffered from progressive hearing loss. His obituary reveals that late in life he did not often go out socially. However, Sarah and her sister, Martha Ann Cushing Esty (wife of William Cole Esty, Class of 1860 and an Amherst professor), were of a livelier bent and are said to have frequently entertained friends and neighbors together. Edward and Sarah had no children, but welcomed extended family into their home, including Frederick Tuckerman, the nephew whose wedding was the occasion for Dickinson’s Sept. 6, 1881 note

Professor of Mathematics William Cole Esty, Class of 1860, circa 1882.  Trustee of the college Edward Tuckerman Esty, Class of 1897, in 1939. |

The brief Tuckerman diary provides a glimpse into Edward and Sarah’s social life, with notes about regular small entertainments, excursions and visits among friends. The Tuckermans and the Dickinsons would have had ample opportunity to become well acquainted between the years of the Tuckerman marriage (1854) and Emily Dickinson’s death (1886), and it is easy to imagine that the families may have exchanged notes throughout those 30 years.

The route back to Amherst for Sarah’s letters included several stops among the generations—a convoluted path the poet would have enjoyed. Ultimately, Thomas Michie found the letters at his late parents’ home in Worcester, Mass., tucked safely in a trunk containing letters, diaries and photographs belonging to his maternal grandfather, Edward Tuckerman Esty (Class of 1897 and a trustee of Amherst for many years). Edward Esty was Sarah Tuckerman’s nephew. His daughter, Martha Esty Michie—Thomas’s mother—had preserved the trunk for years. Thomas Michie knew his grandfather Esty only through family stories, just as he knew his grandfather’s “Aunt Tuckerman”—Dickinson’s “Mrs. Prof Tuckerman.”

Edward Esty was a lawyer who lived and practiced in Worcester beginning in 1902. He made a home there for his widower father, William Cole Esty, and, after 1906, for his aunt Sarah Tuckerman, widowed on March 15, 1886.11 Thomas Michie has observed that life in Worcester for this extended Esty-Tuckerman family, long intertwined with the Amherst community, “must have felt like Amherst-in-exile.”

Professor William Cole Esty, seated between Sarah Tuckerman and Julia Coy Esty, William’s wife. Back row, from left, are Edward, William, Robert and Thomas Esty. Julia is holding her son William, while Sarah Tuckerman is holding a dog, “Tony,” who appears in several photographs of the family. |

When Sarah Tuckerman died in 1915, her nephews Edward Esty and Robert Pegram Esty were co-executors of her estate. Michie recollects that “Aunt Tuckerman” was particularly devoted to her sister’s sons—William, Thomas, Edward and Robert Esty—who had lost their mother, Martha, in January 1887. In dividing her possessions, Sarah gave Tuckerman family heirlooms to her Tuckerman nephews, while her personal possessions went to her Esty nephews. Edward Esty, a family historian and genealogist, inherited her personal papers, and thus the correspondence from Dickinson remained in the house with him. He divided the Dickinson correspondence among himself and his three brothers. Upon his death in 1942, his daughter Martha inherited Sarah’s papers and his portion of Dickinson’s letters. Martha (named for her father’s mother) married Forbes S. Michie, and she in her turn passed the family papers to her son Thomas, who now serves in his grandfather’s role as family historian.

In presenting the Dickinson manuscripts to the Amherst College Library’s Archives and Special Collections, Michie himself has taken the family back to Amherst. He writes:

“The trunk of letters and diaries spent the last 50 years in my parents’ house in Worcester, not far from the Esty home where my mother grew up. I am glad they have found an even better home at Amherst. Better late than never.”

Thomas Michie’s wonderful gift brings these manuscripts home, where they will rest here in the college’s Emily Dickinson Collection, to travel no more.

Daria D’Arienzo is head of Archives and Special Collections. Margaret R. Dakin is Archives and Special Collections specialist. They gratefully acknowledge both Thomas Michie, for sharing many of the details that linked the people in this story, and Ralph Franklin, for his assistance.

Endnotes:

- These manuscripts join, in Archives and Special Collections, other letters, notes and poems from Emily Dickinson to Sarah Tuckerman. This earlier group of manuscripts was given in the 1950s by brothers Robert Pegram Esty (Class of 1897) and Thomas Cushing Esty (Class of 1893) and their nephew John Cushing Esty (Class of 1922 and the son of William Cole Esty [Class of 1889], who died in 1928).

- Robert P. Esty made these photostats for Esty family members; the family later gave some to the college and to the Jones Library in Amherst. In The Letters of Emily Dickinson (Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1958, p. xi), Thomas Johnson mentions letters that “Mrs. Edward T. Esty” owned. In The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson (New Haven, Conn.:Yale University Press, 1960, p. 486), Jay Leyda mentions the collection of “Mrs. Thomas Esty, Worcester.” In The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Variorum Edition (Cambridge: Belknap, 1998, p. 1,593), Ralph Franklin attributes the photostats to Thomas Esty.

- Poems are reprinted by permission of the publishers and the Trustees of Amherst College from the following volumes: The Poems of Emily Dickinson, Thomas H. Johnson, ed., Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Copyright © 1951, 1955, 1979, 1983 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College; The Poems of Emily Dickinson, Ralph W. Franklin, ed., Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Copyright © 1998, 1999 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Dickinson letters are reprinted by permission of the publishers from The Letters of Emily Dickinson, Thomas H. Johnson, ed., Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Copyright © 1958, 1986, The President and Fellows of Harvard College; 1914, 1924, 1932, 1942 by Martha Dickinson Bianchi; 1952 by Alfred Leete Hampson; 1960 by Mary L. Hampson.

- Frederick Tuckerman was the son of Hannah Lucinda Jones and Frederick Goddard Tuckerman, a poet from Greenfield, Mass. Frederick the son and his wife, Alice Girdler Cooper, had a daughter, Margaret, who was the subject of several notes and poems from Dickinson to Alice (“Mrs. Frederick”) Tuckerman. Margaret herself published a volume of her grandfather’s collected poetry and provided access to Dickinson manuscripts that she inherited. Margaret married Orton Clark, whose name also appears in Thomas Johnson’s acknowledgements.

- “The dandelion’s pallid tube” is poem 1,565 in Ralph Franklin’s Poems (p. 1,368). Franklin refers to Todd’s Letters of Emily Dickinson (Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York City, 1931, p. 376), where the note is said to have contained a pressed dandelion tied with a scarlet ribbon. The postmark on the Amherst envelope confirms the November 8 date. The manuscript poem at the American Antiquarian Society was the gift of Mrs. Edward T. Esty.

- In Letters, no. 406, p. 520, Thomas Johnson tentatively dates the letter “[January 1874?]” and notes that the original manuscript could not be located; he therefore used a photostat. Johnson also indicates in his note of publication history that “Mrs. Tuckerman is known to have supplied the dates in letters to her from ED. The occasion that prompted this letter has not been identified.” However, Mabel Loomis Todd states that the occasion was “an apology for tardy congratulations upon Mrs. Tuckerman’s safe return from a long visit in Europe” and dates the letter January 1874 (Letters [1931], p. 369). Interestingly, a diary kept by Martha Cushing Esty, a copy of which is also in Archives and Special Collections at Amherst, confirms the trip and its dates (Diary of Martha Cushing Esty, 1870–1882). The Tuckermans left Amherst for Europe on July 18, 1872, and returned to Amherst on or about December 5, 1873, so it would not be surprising for Dickinson to apologize in January 1874 for a tardy welcome home.

- The joint diary of Professor Edward Tuckerman and his wife, Sarah Eliza Sigourney (Cushing) Tuckerman, January–April 5, 1860 is part of an earlier gift from Thomas Michie to the Archives and Special Collections in the Amherst College Library.

- The highest temperature recorded for this day in the Amherst Weather Records of Professor Ebenezer Strong Snell (Class of 1822) is 19.7 degrees Fahrenheit. He also notes: “Snowing at 9 p.m.: only a film.”

- In addition to biographical files for members of the Tuckerman and Esty families, the Amherst College Archives and Special Collections has the Edward Tuckerman Botanical Papers, 1816-1886, and the William Esty (1889) Papers, 1878-1905. See asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/amherst/ma43_main.html and asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/amherst/ma14_main.html, respectively.

- Tuckerman built the English-style stone mansion in 1856 for $35,000. The house was noted for the Tuckerman monogram and the year 1856 chiseled on a white stone set over the front entrance. In her diary, Mabel Loomis Todd described the wood furnishings in the house. The house was sometimes referred to among the family as “The Tuckerman,” alluding to the frequent visits of friends and family. The Sigma Delta Rho fraternity bought the house in 1913. The college acquired the Tuckerman homestead in 1919 from the Amherst Savings Bank and razed it later to build what is now the Coolidge Cage.

- Professor Tuckerman died on March 15, 1886, just two months before Emily Dickinson (May 15, 1886). The attributed cause at the time, for both deaths, was Bright’s disease.

Photos: All images, unless noted, courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections.