At age 15, half a century ago, I read John Steinbeck’s account of his travels with his dog Charley. The notion of taking off to wander far and wide across America captivated me, but I didn’t have a car. Heck, I didn’t even have a driver’s license.

Shortly after turning 64, I pulled that same tattered copy of Travels with Charley off the shelf and read it again. I had a car, and a license, and in a few months I would have a Medicare card. I also had a best friend, Albie, a yellow Lab mix, a stray who had survived five months in a high-kill shelter before we adopted him in 2012. He was 2 or 3 then, but because dogs age faster than humans, we had arrived together on the cusp of old age. If not now, I thought, when?

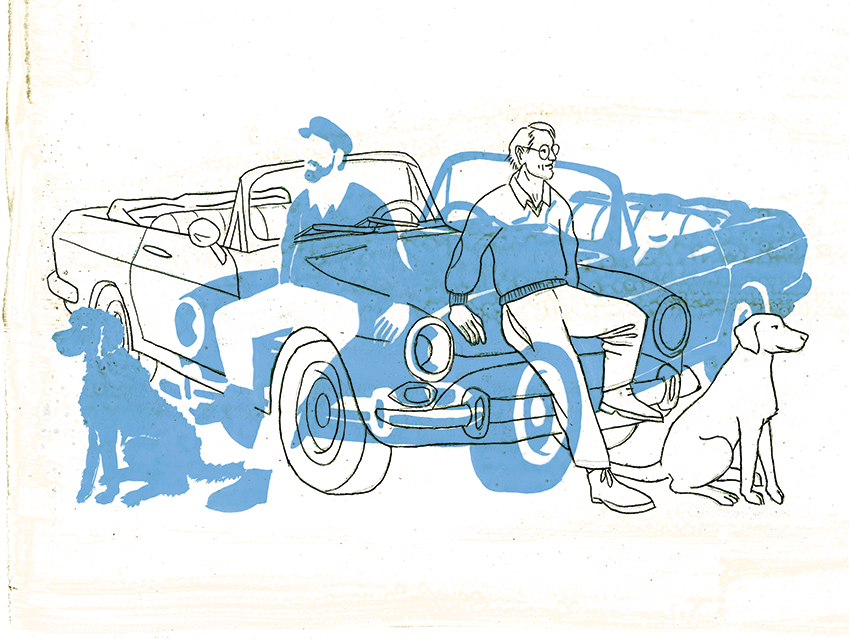

And so, on a cold, cloudy day in April 2018, with the blessing of my wife, Judy, Albie and I piled into a little red convertible and backed out of our driveway in Dover, Mass.

The goal wasn’t to recreate Steinbeck’s journey, but to use his as a touchstone for our own. We had no agenda other than to go over the mountain, so to speak, to see what we could see.

“When we get these thruways across the whole country,” Steinbeck wrote of the interstate highway system, then in its infancy, “it will be possible to drive from New York to California without seeing a single thing.”

So, we hewed to roads less traveled, especially as we made our way south, driving the entirety of Skyline Drive, the Blue Ridge Parkway and the Natchez Trace Parkway. We stopped in Alexandria, La., so the two women who saved Albie’s life could see him again, and in Okemah, Okla., the hometown of my lifelong hero Woody Guthrie.

From there all the way to California, we were, more or less, on the route Steinbeck’s Joad family used to escape the Dust Bowl, until we turned north up the Central Valley to Yosemite. We crossed the virtually uninhabited “outback” of eastern Oregon, the northern plains and the Midwest until we landed in Bennington, Vt.

That night I stroked Albie’s head and told him where we were, and that we’d be going home tomorrow after six weeks on the road. And I told him I loved him.

He looked at me with his deep, dark brown eyes, rested his body against mine and sighed. I knew he didn’t understand. I could have been reading him Robert Frost, or sections of the Internal Revenue Code—it didn’t matter. What mattered was the sound of my voice, that he was safe and that we were together.

We were almost home, but first we had a promise to keep.

A few weeks earlier, in Tennessee, I’d gotten a call from Wini Mason, a dear family friend, age 94. As we talked it occurred to me that visiting Wini and her husband, Paul, at their home in Ogunquit, Maine, was how this journey should end. These people, whom I’ve known all my life, have been like a second set of parents. In my first few days at Amherst, when I felt horribly out of place and unprepared, they came to visit and steady my ship. In our phone call, I promised Wini we’d make Ogunquit our last stop.

Ogunquit is where, on family vacations, I learned to ride a bicycle, to surf a wave and to catch a crab with a dropline. When Albie and I arrived, Wini, Paul and I caught up on family news, Wini mourned my mother (they’d known one another since childhood), and we reminisced about summers long ago. Then Albie and I drove to Perkins Cove, a cozy harbor filled with fishing boats and lobster traps, and a wooden drawbridge across the inlet. I took a seat on a bench, Albie, as always, at my side. How many times had I sat in this very spot and watched the ocean lap up against these craggy rocks?

My mind wandered back across the decades and over the past six weeks. We had more than 9,000 miles behind us and just 90 to go; I had nearly 65 years behind me and an unknown number, but far fewer, to go. And Albie, too, now about 9, was closer to the end than the beginning. All of these journeys were slowly ebbing away.

Then Judy called, snapping my attention back to the present. All those miles, and all of the memories stirred up by the day, caught up with me. My voice cracked, and I fought back tears. So much of my life had passed, some of the best of it right here at this very spot. I felt grief for my parents, both long gone, and for innocence lost. So much had happened since my childhood vacations here. But the view? It hadn’t changed at all.

Albie, sweet, earnest Albie, sat quietly by me for about another half hour. I thanked him for being so patient over so many miles, miles that were, no doubt, far more interesting for me than they were for him. This gentle old soul, once lost in the woods, now part of who I am and will forever be. Then we walked over to the takeout window at Barnacle Billy’s and I bought him a vanilla ice cream cone. And that is how the travelers came home again.

Zheutlin is the author of The Dog Went Over the Mountain: Travels with Albie: An American Journey (Pegasus, 2019), from which this essay is adapted.

Illustration by Maëlle Doliveux