In my line of work, in which everyone strives to be a card-carrying skeptic, no one wants to be accused of writing a love note. A love note, for the uninitiated, is a fawning article, a piece of puffery to which no self-respecting reporter would attach his or her byline. This guidebook aims to be a different sort of love note: a passionate, full-throated appreciation of Amherst’s campus, yes, but also a demanding assessment, one that does not hesitate to call out instances in which the College and its architects have failed to aim high or have fallen short. To me, that’s true love—not blind admiration or rabid boosterism, but an esteem based upon a searching eye, a generous heart and a mind open to all forms of experience.

In that spirit, these pages paint a picture of the Amherst campus that reaches beyond the visual to the multisensory. On the College’s spectacular hilltop plateau, visitors breathe in the same intoxicatingly fresh mountain air that inspired the poets Emily Dickinson and Robert Frost. Pine trees scent that air, especially around the War Memorial, which looks out to the softly sculpted ridgelines of the Holyoke Range. The granite interior stairs that ascend to the elegant simplicity of Johnson Chapel, their treads worn into scalloped hollows by the footfalls of myriad generations, remind students that they’re walking in someone else’s footsteps—and that someone else will walk in theirs. While Amherst is a community in space—an intimate face-to-face college rather than an impersonal university—it is also a community in time. Its history now stretches back more than 200 years, and its campus, seemingly fixed but always changing, exerts a strong gravitational pull: the power of place.

By place, I don’t mean a dot on the map, though this particular dot is about 90 miles west of Boston, in a verdant agricultural valley where the crops include asparagus, sweet corn and tobacco. Nor, by place<, do I mean a self-aggrandizing institution of higher learning that accumulates buildings by famed designers like celebrity autographs, although Amherst’s campus does reflect the mark of such noted architects and landscape architects as McKim, Mead & White, Frederick Law Olmstead, Benjamin Thompson and Edward Larrabee Barnes. By place, I mean a college where the whole and the parts are in equipoise—where the landscape, the buildings, the administrators, the professors, the staff and the students combine to make a whole that is more, much more, than the sum of its individual parts.

Those parts, I hasten to add, include the intangible ingredient of memory, the stories that help bring inert brick, stone and glass to life. This book is full of such stories. There’s the one about Emily Dickinson’s grandfather, Samuel Fowler Dickinson, paying repeated visits to a dying farmer named Adam Johnson and beseeching him to donate his fortune to the fledgling cash-poor college so it could build a proper chapel. There’s the 1938 hurricane tearing out a beloved alee of maple trees, the College Grove, and clearing the way for the present main quadrangle. There are the white fraternity brothers who in 1948 take the principled stand of leaving their national organization after it suspends them for pledging a black student; their white-columned, mansion-like frat house is today the College’s African American theme house. And there are the women who, after coeducation began in 1975–76, deposited flower pots in the urinals of previously all-male dorms to make their presence felt.

Presidents change, as do pedagogies, professors and the profile of the student body. But as long as distinguished buildings and landscapes are not destroyed, they serve as a constant, one that imbues a college with a distinctive character. Amherst’s distinction arises first and foremost form its site—a hilltop that is the highest spot in the town of Amherst. This hilltop, home of the Greek Revival Johnson Chapel and four flanking brick buildings that form College Row, is ringed by hills in every direction—the Holyoke and Mount Tom Ranges to the south and southwest, the Pelham Hills to the east, Mounts Sugar Loaf and Toby to the north, and the approaches to the Berkshires to the west. As George Harris, class of 1866, the College’s president from 1899 to 1912, observed in an essay titled “The Amherst Landscape,” the hills border

Just at the right distance all round to be softened into rich colors of sunset and sunrise, haze and storm, without losing [their] distinctive character. Every season of the year—spring with its bright tender green, summer with its pomps of cloud and foliage, the gorgeous coloring of a New England autumn, and, not least, when the cliffs and bare trees peep out from under their mantle of winter, or it may be are wrapped in a fleecy robe woven by the large wet flakes of a later winter storm—every season of the year, nay, every hour of the day adds, for the observant eye, some phase of beauty unimagined before.

Amherst’s buildings tend toward elemental simplicity, with clean, sharp lines rather than picturesque frills and elaborate silhouettes; they are kin to the simple but powerful buildings of the Connecticut River Valley: the weathered brown tobacco sheds, long and gabled, and the white meetinghouses, set alongside the green carpets of town commons. Many structures, especially those by the Boston firm of Putnam & Cox, which shaped most of the College’s former fraternity houses in the early years of the 20th century, stress the virtues of one building harmonizing with another. The buildings typically are arranged in quadrangles, but unlike their walled counterparts in Oxford, Cambridge or New Haven, the Amherst quads have openings between buildings—they are ventilated, as it were—to take advantage of the panoramic views afforded by the hilltop site. This dual character, a mixture of comforting enclosure and expansive openness, extends to the Amherst Town Common, which is flanked by nearly as many College buildings as the main quad. With the exception of the gates that control access to Pratt Field, no gates guard the entrance to the College, in contrast to urban universities like Harvard or even the Pioneer Valley institutions of Smith and Mount Holyoke Colleges. The absence of such borders is a sign of an ongoing comity between town and gown that dates back to the College’s beginnings.

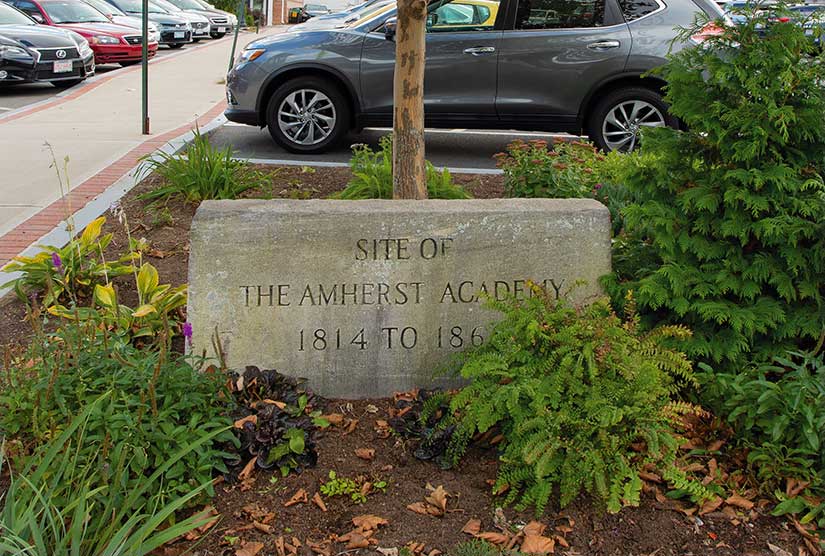

If visitors know where to look, clues to the College’s origins are hidden in plain sight. The first, a raised granite marker next to a Town of Amherst parking lot on Amity Street, suggests that the College’s founding was more of a community enterprise than a breakaway from rival Williams College, as the story is often mischaracterized. The marker commemorates the site of the Amherst Academy, a distinguished (now-closed) secondary school that gave birth to the College. The academy’s leaders, deeply religious men who included the lexicographer Noah Webster, sought to build on its success by starting a college that would train ministers to supply their schools and churches with well-educated teachers and preachers. In 1818, they established the Charity Fund, which would pay the tuition and rooming expenses of “indigent young men of piety and talents, for the Christian Ministry.” Funds poured in from local farms, craftsmen and ministers. Townspeople volunteered their labor in 1820 to construct the institution’s first building, South College (now South Hall). When Zephaniah Swift Moore, Williams College’s second president, resigned from the then-struggling institution in the summer of 1821 and brought 15 students with him to Amherst, he was not so much importing higher education to the Connecticut River Valley as he was becoming the first president of a college whose emergence arose as naturally as the deep green forests that swept over the valley’s hills.

Amherst's proud academic acropolis. From left: Williston Hall, North Hall, Johnson Chapel, South Hall and Appleton Hall.

The second clue to the College’s origins is the orientation of College Row: it doesn’t face east, toward Boston. It faces west, toward the river in whose waters, as the historian William S. Tyler, class of 1830, once wrote, Native Americans “delighted to ply their light bark canoes … and on whose banks they build their most beautiful villages and raised their richest fields of corn.” The Native Americans of the region—the Nonotuck nation in what is now the Five College area, the Pocumtuck to the north, and the Agawam to the south—called this body of water “Kwinitekw,” or “Great River.” It was the interstate highway of its day, and, naturally, the College turned in its direction. European settlers moved east from the river—first to the present Town of Hadley, which was incorporated in 1661, and later to what is now the Town of Amherst, which became the eastern division of Hadley in 1730 and was incorporated in 1759. Like Hadley, Amherst established a Town Common, a long tract of open space that at first was more utilitarian than aesthetic. Crops grew there, and the common served as a military drill ground. Schools like the Amherst Academy clustered along this open space. It was natural for the fledgling college to do the same.

Life at that college, first called the Collegiate Charity Institution, was primitive by today’s standards. The first cadre of 47 students drew water from the College well and cut firewood from the aforementioned forests. The initial course catalog, issued in 1822, consisted of a single sheet of paper. The entire College library was contained in alone case, just six feet wide. Despite the College’s lack of resources—the Massachusetts legislature refused to grant a charter until 1825, owing to opposition from Williams and Harvard Colleges—the founders harbored high aspirations. They called their college “a city set upon a hill,” and they called its hill “a consecrated eminence,” as though it had been blessed by God. In our own time, more secular than theirs, their religious fervor may seem unfathomable. But the built legacy that they and their successors left still engages us. Great places do that. They transcend the worldview of their creators.

Kamin, a Pulitzer Prize-winning architecture critic at the Chicago Tribune, is the author of Amherst College: The Campus Guide (February 2020, Princeton Architectural Press). The book features photography by Ralph Lieberman and a forward by Amherst President Biddy Martin.