For What You Have Been Waiting.

So reads the sign that Niki Russ Federman ’99 shows me during the usual commotion at Russ & Daughters, the small but storied bagel-and-lox shop on New York’s Lower East Side. The place has become a real draw over its century of existence. Everyone from Anthony Bourdain to Jake Gyllenhaal has publicly shown it love, and it’s a stop on urban foodie tours as well as a tender marker of home for generations of New Yorkers. Federman is the fourth-generation co-owner. Her cousin Josh Russ Tupper is the other. And that sign was painstakingly crafted by their great-grandfather.

Joel Russ immigrated here in 1907 from the shtetl of Strzyżów, in what is now Poland, and started selling herring from a barrel to other immigrants in the neighborhood. He worked his way up to a pushcart, then a horse and wagon and, at last, opened the establishment in 1914. A delicatessen it is not. It’s an appetizing shop. The difference lies in kosher rules: An appetizing shop sells fish and dairy but no meat, while a kosher deli sells meats but no dairy. New York used to be chockablock with appetizing shops, but this is one of the few left.

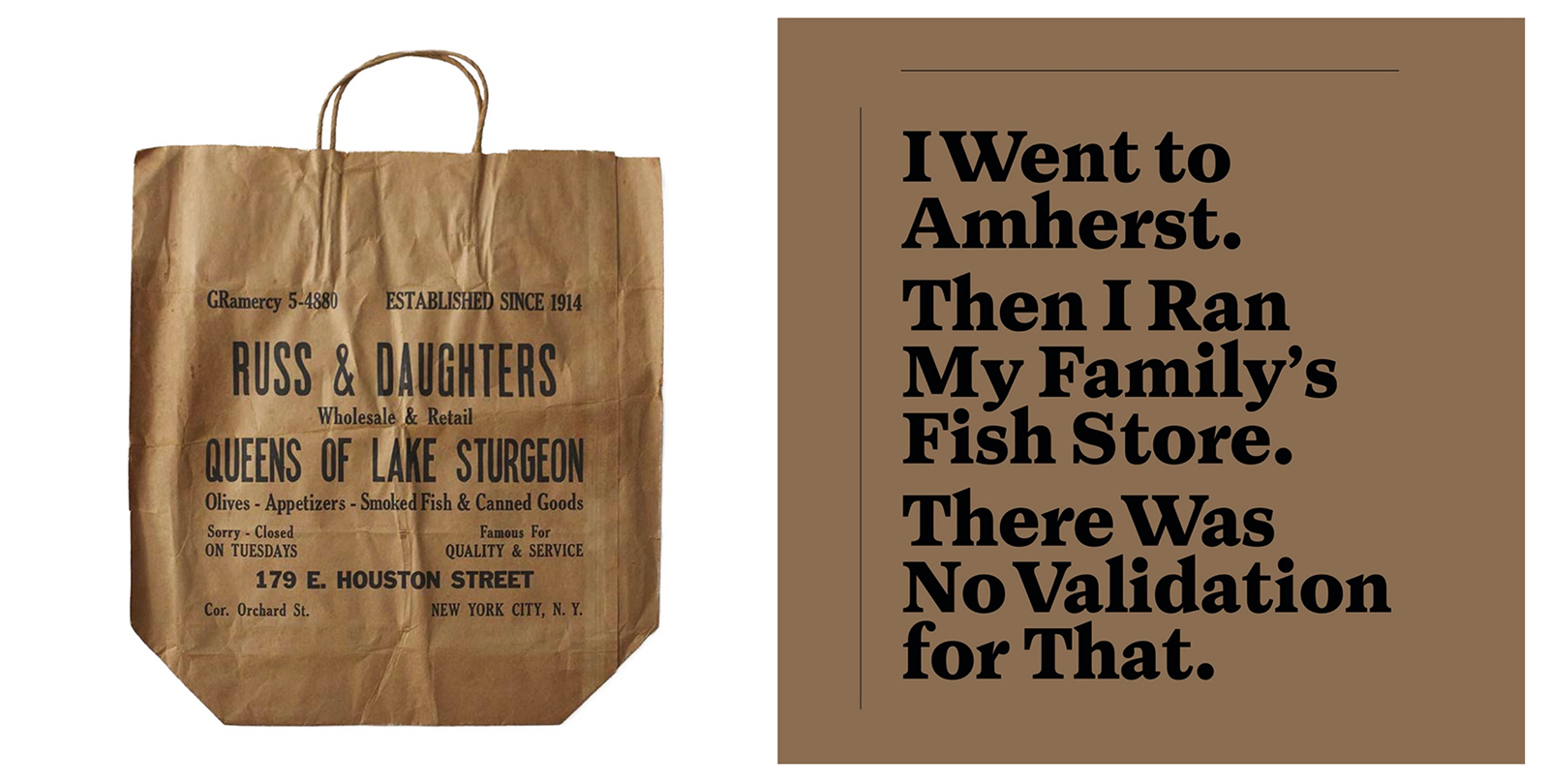

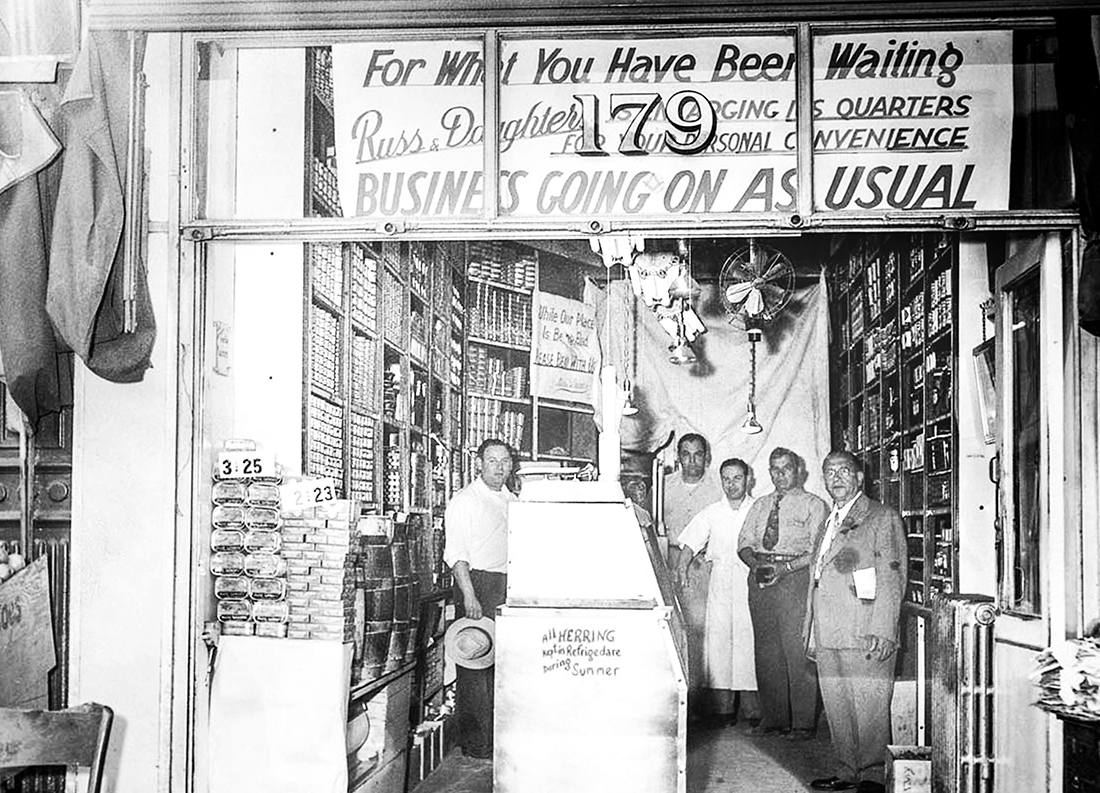

Anyway, Joel Russ displayed that sign, in 1949, to flaunt the reopening of the shop after an expansion into the empty storefront next door. That was pretty much it for expansion until Federman and Tupper took over in 2010. Since then, the family has launched (and this is just a short list) a Russ & Daughters cafe a short walk from the shop, a warehouse, bakery and retail shop* in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, a mail-order business (that quadrupled its sales during the pandemic) and a shop/dining/takeout space that’s expected to open this summer in Manhattan’s Hudson Yards.

Back in 2014, when the cafe was being built, Federman had her great-grandfather’s sign recreated and hung it on the construction shed outside. Again, yes, to stoke anticipation, but also to share an in-joke: “He was a native Yiddish speaker, and he was clearly trying to be very official in the wording,” says Federman with a smile. “I have always loved that sign.”

There are lots of signs to love, actually, at Russ & Daughters: some illuminated on the walls or tucked into bins, for everything from Gaspé salmon to bialys, pickled herring to rugelach, challah to caviar. Federman gamely points out many other sights—the crisp white coats worn by the expert lox slicers, who take months to learn how to carve salmon “so thin you can read The New York Times through it,” as the saying goes; the vintage ticket dispenser; the employees who have worked here for decades. I meet Eduardo and Tomás and many others as Federman toggles between English and Spanish; her mother grew up in Colombia, and she speaks fluent French and some Japanese, too, from studying abroad during her college years.

On my tour of the original shop, she breaks off frequently to greet customers, some she’s known her whole life, others she’s just meeting. They’ve come here from Santa Fe, Australia, San Francisco and just around the corner. One has freshly arrived (as many do) from the nearby Tenement Museum. Another has been dispatched to buy bagels for a family reunion in Pennsylvania. I introduce myself to a man who gives his name as Jeff Preiss and says he’s a regular of 40 years. Later, I realize he’s a filmmaker (1988’s Let’s Get Lost). As the guy next to us gets handed an everything bagel, I ask Preiss to describe his feelings about the shop. “It’s too deep, too deep,” he says, shaking his head. “I always say, ‘I’m never not happy if I’m in this store.’ I walk in and it’s that immediate sensation that is only in Russ & Daughters.”

As a child, Federman viewed the shop’s hand trucks “as my chariot,” she says. “I basically grew up as a ‘shop kid.’ The whole world comes through those doors, and I’d meet all these amazing New York characters.”

The “& Daughters,” from left: Hattie, Ida and Anne, with their father, Joel Russ. Unlike Anne, her grandmother, Federman had many career options. “But I chose to follow in her footsteps. That was really validating for her.”

Family businesses may be venerable or even venal (see: the Roys of HBO’s Succession) but they aren’t always viable. In the U.S., their average life span is 24 years. Only 40 percent are passed on to the second generation, with 13 percent managing to survive through the third.

How many family businesses last, like Russ & Daughters, to a fourth generation? Just 3 percent.

Family businesses may not go far—but they do go wide. The figures above and below come from the Cornell SC Johnson College of Business website: There are 5.5 million family businesses in the United States, and they supply 57 percent of the nation’s GDP, employ 63 percent of the workforce and provide 78 percent of all new job creation. You may think of mom-and-pop stores, but some of the country’s biggest corporations are family-run, including Walmart and Ford.

Another stat puts Federman in context. According to a 2022 report by the Women Business Collaborative, 7.4 percent of Fortune 1000 companies are led by women. But in family businesses, according to those Cornell figures, some 24 percent are led by women. And Federman runs one with that rarest of attributes: women referenced in the family business name. (Can you think of another one with “Daughters” in the title? Russ & Daughters staffers are trying to identify others; so far, they’ve found just a handful*, and Russ & Daughters is the first.)

Joel Russ originally used the name J. Russ National Appetizing, and then Russ’ Cut-Rate Appetizing. He had no sons, only daughters, and when Hattie Gold, Ida Schwartz and Anne Russ Federman (to use their married names) sliced salmon and worked behind the counters, they did so with great skill and were better at charming the customers than their cranky father. In the 1930s, partly to distinguish his business from his competitors, Joel made the three women full partners (yet another rarity) and changed the name to Russ & Daughters.

In 2014, a documentary called The Sturgeon Queens came out about the business and the family. The surviving daughters (Hattie, 100 at the time, and Anne, then 92) “act like the Golden Girls in it,” cracks Federman, and various fans weigh in. The late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg recalls how taken she was by the Russ & Daughters name as a girl. “Everything else was ‘Shmuel & Sons,’” she said. “Even before I heard the word feminist, it made me happy to see that this was an enterprise where the daughters counted just like sons counted.”

Fifty-pound sacks of carrots. Or potatoes. Or onions. When Federman was a child, she loved how important she felt meeting deliverymen at the Russ & Daughters door. She’d direct the men to the kitchen, watch them offload, then clamber up the bumpy, baggy mountains. Sometimes her folks sent her to the bakery next door to fetch a roll of quarters. Later, they’d let her take phone orders. “My brother and I were ‘the kids at the store,’” she recalls. “I watched my parents work. It was an education for me.” Mark Russ Federman, father of Niki and son of Anne, took over in 1978 when the second generation retired. He ran the store with Niki’s mom, Maria Carvajal Federman.

We’re in a booth at Russ & Daughters Cafe, having lunch. Her last-minute email to me this morning was “Come hungry!” While I sample the creamy Hot Smoke / Cold Smoke salmon spread and latkes with sour cream and salmon roe (all so good), Federman tells me that she grew up in Park Slope* and attended the private school Saint Ann’s. That’s where she connected with Melissa Feuerstein ’93, then teaching photography there. “We spent all this time together in the darkroom, and she would tell me stories about Amherst,” Federman recalls. “I really looked up to her, and I was captivated by her experiences there.”

At Amherst, though, it took her a while to find her footing. “I felt like I didn’t fit into any specific box,” she says. “I wasn’t an athlete, and I wasn’t an artist.” She thought it might help to join the golf team, having hit the links during summers visiting her mother’s family in Colombia. “I had a really nice swing, but I’m this kid from Brooklyn. I’m up against all these girls who’ve grown up in country clubs.”

She pauses to read a text. A customer on a Delta Airlines plane has sent a photo of the in-flight menu, which includes a “Russ & Daughters Smoked Salmon and Bagel Plate.” Delta is one of many clients, Federman explains. Russ & Daughters supplies the salmon for several high-end Jean-Georges restaurants, too, and catered the wrap party for the TV series The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel.

I guide her back to Amherst. She majored in political science and quit the golf team. I asked if another group helped lift her social life. “The Hillel dinners were the best meal of the week,” she says. Food salts our conversation in unexpected ways: When I asked about favorite classes, she named “The Anthropology of Food,” taught by Deborah Gewertz, the G. Henry Whitcomb 1874 Professor of Anthropology. “I think I was drawn to it on some subconscious level, finding my own entryway to think about food on a more intellectual level.”

She wrote one paper on death row inmates’ last meals, and another on the intricate food system behind caviar. Gewertz scribbled in the margin of the latter: “You need to turn this into a book!” That hasn’t happened, but Federman and Tupper have taught a few classes on the history and terminology of the caviar trade. Gewertz is a Russ & Daughters customer now, Federman reports, as is Ilan Stavans, the Lewis-Sebring Professor of Humanities and Latin American and Latino Culture.

“Not only was he an incredible professor, but I really connected with him, because he’s a Mexican Jew and I’m a Colombian Jew,” she says. Stavans was especially interested in the heritage of Federman’s mother, though she has no known link* to Luis de Carvajal the Younger, who wrote the first memoir of a Jewish person in the Americas. In 2019, Stavans published The Return of Carvajal: A Mystery.

We squeeze in more conversation, but soon are squeezed out by Federman’s family and friends who are lunching here too. Her dad, holding court in the back, jokes to me that he’s “the guy who paid for Amherst,” adding, “Make sure you write that Niki has herring in her DNA.” Then I meet the director of programs for New York’s Film Forum, the head of the American Jewish Historical Society and the rabbi who presides over Passover seders at the cafe. One friend, Stefanie Halpern, director of the archives at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, speaks of the business’s connection to Yiddish heritage: “Russ & Daughters is an easy first entrance point for people. It’s a powerful way of connection. I’m in charge of taking care of the archives, and these documents are not alive. But you come to a place like Russ & Daughters and you feel the aliveness of history.”

As I sip my pineapple shrub (a retro soda, with fruit juice carbonated by a bit of vinegar), another text pings. It’s from Israeli actor and comedian Ori Laizerouvich, who’d just filmed his trip to Russ & Daughters for one of his Jewish Foodie web episodes. As Federman reads it, I notice the historic black-and-white photos on the wall. I ask who’s who, and she tells me, but I’m struck by what she says next: “It’s very intentional that there are no labels on these pictures. People don’t necessarily see my great-grandfather up there—they see their own immigrant ancestors. It’s about being universal.”

“I’m lucky that, literally every day, a customer tells me how much the shop means to them,” Federman says.

Who knew an errand would be so revealing? Lunch over, Federman and I walk a few blocks so she can examine her newly repaired eyeglasses at Moscot, a family-run optical shop now on its fifth generation. Then we get into Federman’s car to drive to the Brooklyn Navy Yard warehouse, and she mentions that she leases the car from Biener Audi, a fourth-generation family business in Long Island. I point out the obvious pattern. “I feel a kinship,” she explains. “I’m passionately interested in getting to know other multigenerational family businesses.” She has pitched a docuseries about multigenerational family food makers from around the world. Apple TV+ said yes, then no, but Federman hasn’t given up hope—and she was thrilled to meet two other women who are the first to run their respective family businesses, namely Paris’s Poilâne Bakeries and Kyoto’s Honke Owariya soba noodle shop, begun in 1465.

I’d just seen this affinity play out at the cafe. The family in the booth across from us couldn’t help but eavesdrop on my interview, and the dad, Brett Stern, told us that he’s the third generation in his family’s business, Lord Daniel Sportswear. As he and Federman discussed the relative merits of working with relatives, I asked Stern’s teenage daughter how she felt about all this family business talk. “It’s really cool to hear about stuff that my dad and his whole family have been a part of for so long,” she said. “But I definitely want to choose my own path.”

Federman wanted that, too. “I was never made to feel that there was any expectation that I would take over,” she says. “I think my father, not so secretly, saw me as his natural successor, because he saw that I had the same kind of emotional attachment, the same love, for the people in the community. But it was never put on me—and then my mother actively discouraged me after I got out of Amherst. I was educated and told to go and do whatever I wanted.”

That was how it rolled for all of Federman’s immediate family: Before assuming ownership at Russ & Daughters, Mark had been a legal aid lawyer and prosecutor, and Maria had been a research chemist. Federman’s only sibling, Noah Federman, is an oncologist and has opted out of the family business.

As for Niki, to paraphrase her great-grandfather’s sign, for what she had been wanting? “I was enamored by the thought of working in the art world,” she says. “That felt much more exciting and sexy to me than working in the family business.” After Amherst, she became the executive assistant to the director of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. “Part of my decision was to get as geographically far away from Russ & Daughters as I could within the country—but even then, I couldn’t escape.” Indeed. Her boss, who had lived in New York, hinted that Federman could expedite his orders from Russ & Daughters. And the mom of the family who initially hosted her in the Bay Area drove her to an empty storefront and suggested that’s where she could launch Russ & Daughters West.

When Federman moved back to New York, she immediately regretted what seemed like a regression. At least she didn’t work at the shop, having taken a job at an NGO that partnered with the United Nations to combat extreme hunger, but she did live above the shop in a studio apartment with her then-boyfriend (now husband) Christopher Meehan. She’d first met him at Amherst, on the steps of Newport House, when he was vising his brother Matthew Meehan ’98. (Christopher is now a psychotherapist. They have two children: Maya, 11, and Elan, 6.)

Meanwhile, Federman’s father was talking more fervently about retirement. And then 9/11 happened. “We went up to the roof, and unfortunately I saw too much,” she says. At 179 East Houston St., the shop had a direct view of the twin towers. “It was just a parade of people fleeing downtown and heading uptown. We stayed open and were giving people water, a place to rest and regroup.” For weeks afterward, the street became an emergency corridor.

She pitched in at the shop, saying it was a temporary thing, but “my father took that as his exit strategy.” He told her that either she—then 24 years old—had to take over or he would have to sell the business. “It was very shocking,” says Federman. “And it created a lot of tension between us. My father, who I adore and who I thought always wanted the best for me, was all of a sudden using me to save himself. It felt like my world got so small.”

So she played her last card and applied to business school, which could be read (or not) as preamble to managing the shop. “I felt that business school was an acceptable exit. I needed to save myself and my relationship with my family.” She got into the Yale School of Management with an essay describing how she would modernize Russ & Daughters by opening new locations and starting up e-commerce. “I thought it would be compelling for a business school application,” she says. “But I didn’t believe it, because I was in the midst of my own existential angst and crisis.”

In the early aughts, the food business did not have the cachet it has these days. “It might be OK to go to Amherst now and later open a restaurant, but that wasn’t the trajectory when I was there. Going to private schools like St. Ann’s and Amherst, there wasn’t the social validation to make me think that coming home to run my family’s fish business was a worthwhile application of my education. I remember there were customers who would say, ‘Oh, didn’t you go to Amherst? What happened to you? How did you end up back here?’”

Federman quit Yale in her first semester. The truth is, she says, none of the alternatives to Russ & Daughters—the museum job, the NGO job, business school—“felt real to me.”

Joel Russ came up with this sign in 1949 when the original storefront was being renovated. “He was a native Yiddish speaker, and he was clearly trying to be very official in the wording,” Federman says. “I have always loved that sign.”

We’re now at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, an imposing site on the East River teeming with docked tugboats and big, burly buildings from World War II. Since the military left, those structures now house some 500 businesses, among them, since 2016, Russ & Daughters, which leases 18,000 square feet inside Building 77.

Here we meet the salmon slicers, who call themselves “the ladies who lox,” and Federman shows me the multiple stages of bagel-making, including the “bagel sauna,” a glassed-in room where the doughy circles rest in wet heat. As I sample some raspberry rugelach, Federman tells me the rest of her story. Spoiler, not spoiler: She eventually opted to join the business—but the timing was tricky. While she was agonizing, Josh Russ Tupper (one of her six cousins) reached out to his Uncle Mark. Tupper had been an engineer working on semiconductors and, like Niki, felt frustration with his job.

Mark worried that his nephew had too romantic a notion of working in the food business. During this interim, after much thought, Niki had a change of heart. “I started to think about the concept of legacy,” she explains. “And I realized that I’m actually part of a lineage, and that Russ & Daughters doesn’t need to be this thing that’s stagnant or set in stone. It can evolve and can grow, as long as I appreciate and preserve the things that are the continuous throughlines.”

Her friend Alice Huang ’98 watched Federman’s struggle up close. “Niki is such a philosophical person and a thinker, a questioner,” she told me. “For her to have taken this business over, she had to make it a really creative endeavor. She may be chill, but she’s also ambitious.”

Niki and Josh decided to take the plunge as partners, splitting responsibilities. He leans toward finance, technology and systems management, and she toward human resources, hospitality and communications; she’s even repurposed her museum skills to curate the art in the cafes. She has also partnered with the Jewish Museum to run a kosher Russ & Daughters restaurant on-site for five years, adorned with a Russ-themed mural by Maira Kalman.

The two cousins joined the business in 2006 and assumed ownership in 2010. Since then, the Smithsonian Institution has designated Russ & Daughters “a part of New York’s cultural heritage.” Federman was named one of the Transformational Women of 2022 by Family Business Magazine and was inducted into the Manhattan Jewish Hall of Fame. And the business is getting a new shot of fame, too. A scripted series on Russ & Daughters is in the works for Time Studios.

Renown is part of the Russ & Daughters story, but so is letdown. The first, second and third generations withstood the 1918–19 flu pandemic, the Depression, World War II and the 1970s decline of the city, while this, the fourth generation, has faced Hurricane Sandy and another pandemic. Under COVID, Federman got political: She joined a newly formed group of fellow restauranteurs in what would become the Independent Restaurant Coalition. The IRC helped spur the creation of the federal government's $28.6 billion Restaurant Revitalization Fund, part of the American Rescue Act.*

With schools closed, Federman brought Maya and a friend to work, and set them up for remote learning in a room at the Brooklyn warehouse, which they dubbed NYU, for “Navy Yard University.” After class, Maya would help pack orders or taste-test new recipes. “She’s got opinions,” says Federman of her daughter, with a laugh. “She’s got a really good palate, too, and derives a lot of joy from being around the business. There’s a glimmer. But, you know, she’s also just 11 years old.”

It’s worth mentioning that there are several children in the fifth generation. “Down the road, I will do succession differently—if there is a succession,” says Federman. “It’s a big question mark. That’s the way it is with all family businesses. But I have to delude myself into thinking that there will be a next generation. Because that’s what you’re working toward.”

It is for what, in other words, she will be waiting.

Katharine Whittemore is Amherst magazine’s senior editor.

Photographs by Beth Perkins

*This article has been corrected from the original to include that the Brooklyn Navy Yard site has a retail shop, to reflect that there are a handful of other businesses with "& Daughters" in the name, and to state that Federman grew up in Park Slope and that her family has no known link to Luis de Carvajal the Younger. It also has been corrected to clarify the work of the Independent Restaurant Coalition and her role in that organization.