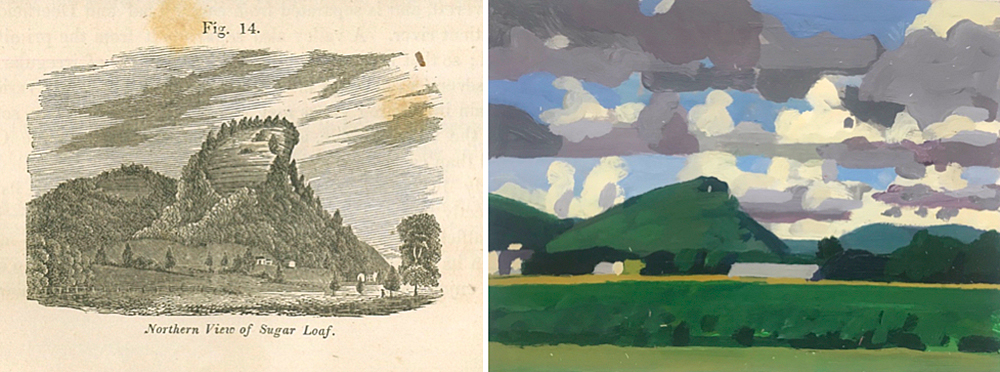

David Gloman, senior resident artist in the Department of Art and the History of Art, spent the summer of 2018 painting the natural scenery of the Connecticut River Valley of Western Massachusetts. His goal? To recreate landscapes that Orra White Hitchcock—regarded as one of America’s first female scientific illustrators—had painted nearly two centuries ago.

The result is Re-Presenting Nonotuck: The Landscape Paintings of Hitchcock and Gloman, an exhibition of works by Hitchcock alongside recreations by Gloman that depict natural scenes in and near Amherst. The exhibition is about observation of the environment, Gloman says, and how natural landscapes change over time. It also pays homage to the Nonotuck and Pocumtuck peoples, who first called the valley home. “I understand how fragile and precious [the environment] is at this point,” Gloman says. “I feel like I’m doing, in a roundabout way, an act of preservation and conservation by painting these places and having people respond to them.”

To re-create Hitchcock’s works, Gloman consulted with Kurt Heidinger, director of the Biocitizen School of Field Environmental Philosophy based in Westhampton, Mass., to identify works by Hitchcock and the places she would have stood to create them. They visited the College’s Archives and Special Collections, which holds the largest collection of Hitchcock’s original artwork. Then they selected eight works and literally went into the field to identify the exact spots where Hitchcock would have set up her easel.

“The most striking thing was trying to find the actual places where she had stood,” Gloman says. In some instances, Gloman couldn’t position himself exactly in the right place, in some cases because of new tree growth and in one instance because of Interstate 91. But in other locations, he was confident he was standing in more or less the same spot. “It gave me chills knowing she was looking exactly at this thing I’m looking at now,” Gloman says.

Hitchcock’s paintings illustrated the scientific research of her husband, geology professor Edward Hitchcock, who was the College’s the third president. The paintings Gloman recreated were published in Hitchcock’s 1841 monograph Geology of Massachusetts. “He was trying to find geological or scientific proof of the Bible,” Gloman says, which factored into the ways Orra saw and depicted her subjects. “She had an appreciation for nature, and the structure of nature,” he says, “and the artistic talent to make these places feel alive.”

In his course “Translating Nature: Drawing, Painting and Sculpture,” Gloman and his students similarly explore connections between art and science. “It’s about looking at things and understanding natural structures, like why certain trees spread out in a particular way or why a leaf is a different color on the top than on the bottom,” he says. “We look at natural objects and analyze what they look like, and we try to infer why.” In this way, students begin to understand how to look at scenes holistically rather than in pieces, and to think about objects in relation and in connection to one another.

Gloman also aims to teach his students a few life skills in the classes he teaches. “Art is about planning, changing your mind once you’ve started and giving yourself the freedom to explore, try something new and to make mistakes,” he says. “It’s also about feeling empowered to have a voice and a point of view.”

Re-Presenting Nonotuck: The Landscape Paintings of Hitchcock and Gloman is on view in Frost Library at Amherst College through Oct. 29.

Visit Professor Gloman’s faculty profile to learn more about his work and courses.