Just two weeks into the fall semester of 2017, Catherine Sanderson, Amherst’s Manwell Family Professor in Life Sciences (Psychology), learned from her son that a student at his college had died after drinking heavily and injuring his head in a fall. One detail of the story was horribly familiar: Though fellow students watched over him, they didn’t call emergency services for nearly 20 hours, by which time it was too late.

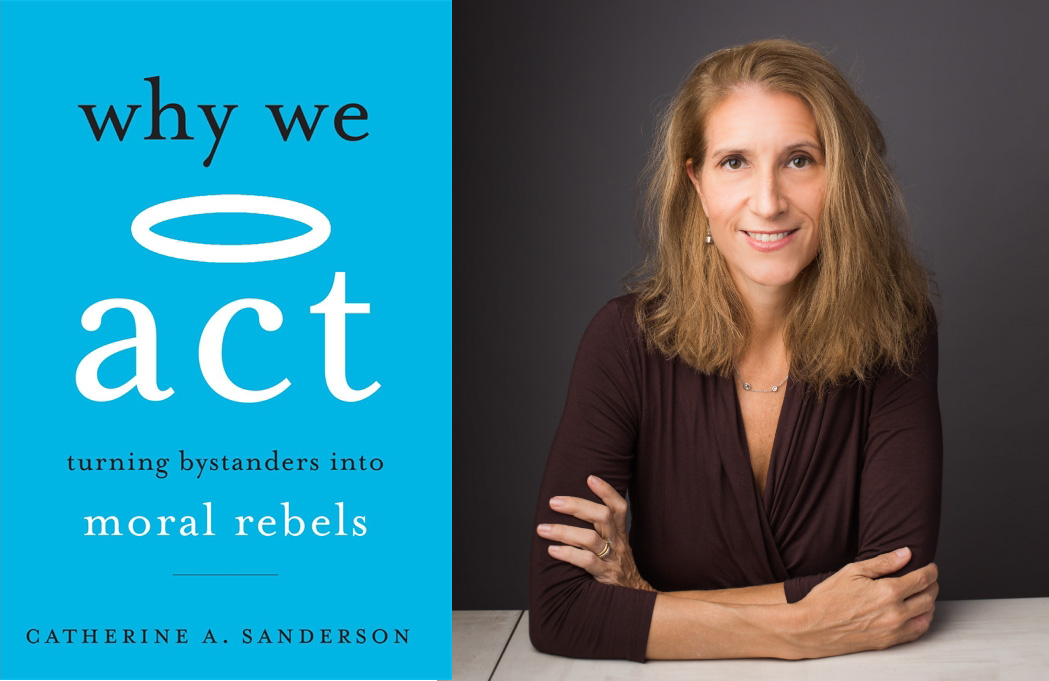

Looking at this tragedy, and news events involving serial sex offenders, school bullies and workplace corruption, Sanderson decided to tackle the question: Why is it that things can go so badly when human beings are put together in groups? In her new book, Why We Act: Turning Bystanders into Moral Rebels (Harvard University Press), Sanderson examines what social psychologists call “the bystander effect,” where the presence of others actually discourages a person from helping in an emergency.

I recently spoke with Sanderson about her book.

Q: I am a full-grown adult just learning now, reading your book, that the story about Kitty Genovese, murdered in 1964 while her Queens neighbors hunkered down and did nothing, isn’t true.

A: For those who majored in psychology, it was a truism, presented in a very black-and-white way by The New York Times, that no one came to her aid, that no one did anything. It certainly is the case that some people did not come to her aid, but it also is quite clear that some people did call [for help], that somebody was with her when she died. The story is more nuanced than it was described. The phenomenon of the bystander effect is more complex.

Q: One can read these accounts of bystanders and conclude: These aren’t very good people. I wouldn’t behave like that. But are you saying our wiring can muck up the best of intentions?

A: What I think is extraordinarily important for us to understand is that in lots of situations, good people do bad things, or good people fail to step up in the face of bad things. It’s not simply a reflection of whether you’re a good person or a moral person or a religious person. There are lots of factors in a situation that can make it really hard to do what, even on some level you might recognize, you should do.

Q: You describe the fear of speaking out as being like physical pain. What’s the connection?

A: What recent research and neuroscience has shown us is that a lot of these processes are in fact hardwired in the brain. Feeling social pain, being ostracized, rejected from your group, is processed at a neurological level in exactly the same part of the brain where physical pain is processed, the same as the pain of stubbing your toe. What it suggests is that it’s not as simple as standing up and helping this person. It feels really, really painful to do so [when helping might bring negative social consequences].

Q: In the book, you note how social pain makes it particularly hard for teenagers to challenge bullies. And yet there’s been research, you say, which suggests that we can use peer pressure for good.

A: Researchers from Princeton, Yale and Rutgers identified basically who the influencers were [in several New Jersey middle schools], and they recruited these students and only these students, and led them through a series of programs on creating a kinder, gentler environment in the school. And they measured [30 percent lower] rates of bullying in the schools. It’s such a profoundly important study because what it suggests is that you don’t have to train everybody—you just have to pick the right kids.

Q: What are some of the key factors that can transform bystanders into “moral rebels”?

A: I think it’s important to recognize that my book is not one-size-fits-all, but here are some things that we know matter:

One, increasing empathy. I have a blog for Psychology Today called Norms Matter, and a piece that I did there looked at how we get people to wear [COVID-19 protection] masks. What the research on changing norms would say is: You don’t [tell people who are resistant to wearing masks], “You’re a bad person” or “You hate America.” You try to make it about you, not them. So you say, “Listen, I know you might think I’m overreacting, but my mom has cancer,” or “my child has asthma,” or “I’m a health care worker and I have to stay safe.” You’re trying to create empathy.

Two, finding a friend. It’s much easier to stand up to any kind of bad behavior if we don’t have to be the only one. Find a friend in your fraternity, on your team, in your workplace, on public transportation—whatever it is—who can speak up with you, who can stand there with you.

Three, sweating the small stuff. In many, many cases of bad behavior, people don’t speak up, because “Oh, it’s just a little thing.” The problem is, once you haven’t spoken up a few times, it becomes very, very difficult to then ultimately speak up when you really need to do so. As bad behavior escalates over time, it’s like the “frog in boiling water” effect. It’s really important for people to try to speak up about little things, so those little things don’t escalate to bigger things.