Amherst was a shock to me,” Tong said, remembering his first days on campus. He arrived in Western Massachusetts, with its rolling hills and cow farms, from Beijing, a metropolis nearly three times as populous as New York City. He describes his first semester as a “high point” of his college career. He delivered a TEDx talk on poetry and social media. He got into the Choral Society, despite having only learned to read clef notation five days before his flight across the Pacific.

The next semester, when the pandemic hit and the College emptied out, Tong found another new passion: He began to take photographs of the

deserted campus and submit them to the Communications division, transmitting glimpses of the Pioneer Valley to a College community scattered across the world.

Tong says that his photography in those months helped him connect to a campus that became “both foreign and oddly homelike.” The photographs also epitomized his approach to Amherst more generally: “Nobody else was submitting

pictures to Instagram,” he remembers thinking, “so I might as well just do it.”

Again and again throughout his four years on campus, whether he was designing and teaching informal courses on Chinese poetry, or serving on at least five College committees, or coaching the Model United Nations team, Tong lived that philosophy: I might as well just do it. With few students on campus in 2021, he volunteered to serve as an admissions tour guide. That year, he also worked as an event planner for the Office of Student Affairs and as a community adviser in James Hall. Tong concedes that this sense of duty might have been born, to a certain extent, out of his desire to seek “distraction from realizing the fact that I’ve been stuck on campus forever.”

But those who know him emphasize his deep and genuine desire to help others. David Ko, director of Amherst’s Center for International

Student Engagement, recalls that Tong, who served for three years as an international-student orientation leader, spent hours on international-student move-in day ferrying red carts loaded with luggage between Alumni House and the First-Year Quad. By the end of the day, Tong was soaked in sweat and out of breath, but he was also smiling ear to ear, still excited to help the next student who arrived.

He became a mentor for younger students

attempting to make a home at Amherst. As Ko points out, Tong even has his own online scheduling service, which students use to set up (for free, Tong emphasizes) meetings about classes, internships and issues related to campus life. In an attempt to save pre-pandemic institutional knowledge, Tong also wrote a 50-page guidebook for international-student orientation, covering issues from navigating Logan Airport to utilizing the academic supports available on campus.

Ko goes so far as to describe Tong as the pride of the international community at Amherst. “International students often think they are international students first, and then Amherst students,” he says. “What Haoran taught us is that, ‘No, we are Amherst students first. We can enjoy all these resources—plus we are international students.’”

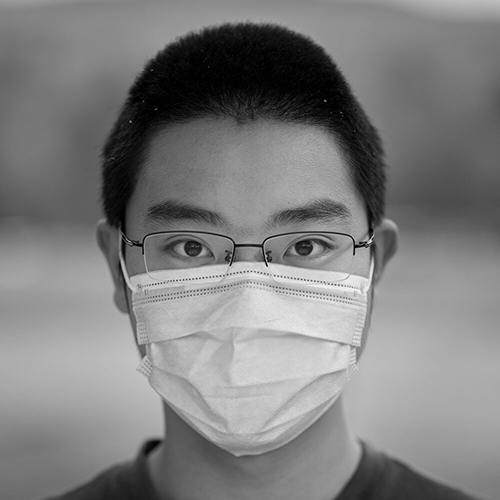

Those who know Tong seemed genuinely grateful to speak about him. Photo by Maria Stenzel

Yet to describe Tong by any one of the identities or skills he brought to the campus community—as an international student, a mentor, a poet or a scholar—is to miss so much.

His LJST thesis adviser, Senior Lecturer David Delaney, had a quote carefully prepared ahead of our interview: “Haoran has more sides than a dodecahedron,” he said, proudly. (A dodecahedron has 12 sides.)

Here’s a sampling of Tong’s academic work at Amherst: He wrote an award-winning paper on the history of bubble tea. He examined the legal implications of global markets for surrogate pregnancies. He applied Confucian generational

ethics to population theory. He TA’d four economics classes. To bolster the offerings in the Chinese department, he designed and taught three not-for-credit courses. As a Schupf Fellow, he helped Ilan Stavans, the Lewis-Sebring Professor of Humanities and Latin American and Latino Culture, put together an anthology on the particularly American strain of the English language. He shared and interpreted Chinese texts for a project on rights-based international law for Adam Sitze, the John E. Kirkpatrick 1951 Professor in Law, Jurisprudence and Social Thought. He assisted Assistant Professor of Economics Mesay Melese Gebresilasse with an analysis of Rwanda’s system of performance contracts for public officials.

Tong’s theses both approached a similar topic—antitrust regulation—but from different perspectives, and each thesis was, within itself, interdisciplinary. The economics thesis considered how algorithmic pricing, in which companies like Amazon use data to provide each shopper with a unique price, impacts consumer welfare. He says he intends it to provide “a clear guideline for the U.S. enforcement agencies” regarding the circumstances under which algorithmic pricing would have either pro- or anti-consumer effects.

Tong’s LJST thesis approached algorithmic pricing from a totally different angle. Delaney, who worked closely with him on the LJST thesis, describes it as a complex but tightly argued treatment. In it, Tong traces the conceptions of antitrust regulation that have predominated in different periods of American history. For Tong, this is a history of metaphors: At one point, for example, monopolistic firms were imagined as octopuses, slowly encircling smaller companies and the levers of power. In tracing this history, Tong applies an almost literary approach to the law. Focusing on metaphor, he draws on the work of cognitive linguists to argue that thinking and reason are inherently metaphorical, that humans can understand new things only by applying models of the world based on things they have learned before.

It’s hard not to see a connection between this

position—that metaphor is the basis of reason—and Tong’s broader commitment to living poetically. It is not that one side of him writes verse and the other writes theses; for Tong, rhetoric and reason are not opposites.

It is worth noting how excited those who know Tong were to speak to me about him. All were happy to set aside the time in a busy part of the year, and all seemed genuinely grateful to have the opportunity to reflect on his impact on the College.