On the occasion of Amherst’s Bicentennial, we present an excerpt from Eye, Mind, Heart: A View of Amherst College at 200, one of the keepsake Bicentennial books commissioned by the College.

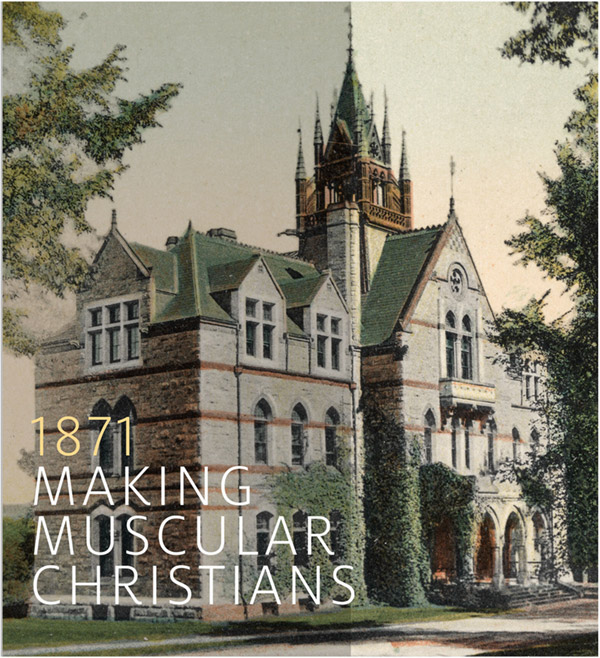

Walker Hall, built of local granite, opens in 1870. The College’s “Temple of Science,” it will burn down a decade later, then rise from the ashes. (Brian Meacham Collection of Amherstiana)

WELCOME TO AMHERST.

The College is still mourning those who died in the Civil War. There are 37 altogether, including Frazar Stearns, class of 1863, son of Amherst College president William Stearns.

But 1871 belongs to a time of Reconstruction and rebuilding. “Muscular Christianity” is a national trend, and Edward “Old Doc” Hitchcock Jr., class of 1849, son of the College’s third president, returns to Amherst with ambitious ideas about physical education after graduating from Harvard Medical School. And so four times a week, you must head to Barrett Gymnasium to perform calisthenics and lift barbells with your classmates. Accompanied by piano, no less.

On campus, scientific interest has risen. Walker Hall, the College’s new “Temple of Science,” has just been completed in 1870. At the same time, however, the College remains extremely devout: 40 percent of Amherst’s graduates have become ordained ministers—an extraordinary number, even for that era.

Amherst is not yet highly selective, but to enter you must have a solid background in the classics. Admission entails traveling to campus to take a written exam given twice yearly, and presenting testimonials of your “good moral character.” As in 1821, you must still be able to parse works in Latin (Virgil, Cicero) and in Greek (Homer’s Iliad and Xenophon’s Anabasis). Math requirements have gotten stiffer. Beyond “vulgar arithmetic, (i.e., fractions) you are now examined in geometry and algebra. English grammar has also been added to the admissions test — including orthography and orthoepy (the proper pronunciation of words).

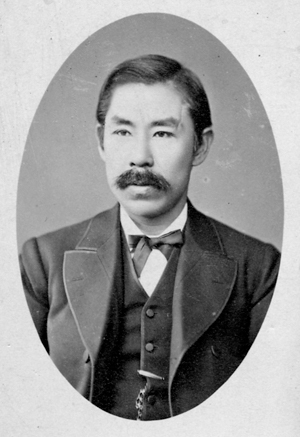

Joseph Hardy Neesima, Class of 1870 (Amherst College Archives & Special Collections)

Of Amherst’s 244 students, nearly half hail from Massachusetts. But the College is also starting to draw students from farther afield, especially the mid-Atlantic and Midwest. There are seven international students, mostly sons of missionaries. Amherst’s first Asian student, Joseph Hardy Neesima, graduated in 1870; he will go on to found Doshisha University in Kyoto.

And in 1873, Amherst’s first African American student since the Civil War will arrive: Madison Smith, class of 1877. At mid-century roughly one-third of Amherst’s students received scholarships. With the Industrial Revolution gaining steam, however, Amherst is fast becoming a college for well-heeled young gentlemen.

If in 1821 there was little to do besides study, now you can choose among extracurriculars, from the Shakespeare Club to the Pedestrian Club. There are two Eating Clubs — students still take their meals off-campus — including one wittily called Eta Nu Pi. Some of the College’s most enduring institutions are already in place, like The Olio yearbook (launched in 1855); The Glee Club (1865); The Amherst Student (1868).

There are only two sports teams: baseball and crew. In 1872, Amherst’s crew team wins the national collegiate championship. The Boston Herald reports that the roads near the Connecticut River race are thronged with a “continuous stream of carriages of every description.”

More than half the upperclassmen belong to fraternities, still called secret societies. Mandatory morning chapel, held daily at 7:50, continues to be a sore point. There are also complaints about cheating. “The A’s and B’s are always directly under the eye of the professor, and a more virtuous set of men cannot be found,” writes one student to the Amherst Student. Meanwhile, students with S – Z names sit in back, where they have “the finest opportunities for ‘cribbing’ and ‘ponying’ that a heart could wish.” (“Ponying” means cheating from a literal translation.) The writer suggests changing the seating order once a term. Note: By 1871, Amherst’s dropout rate is high, with more than one-third not graduating.

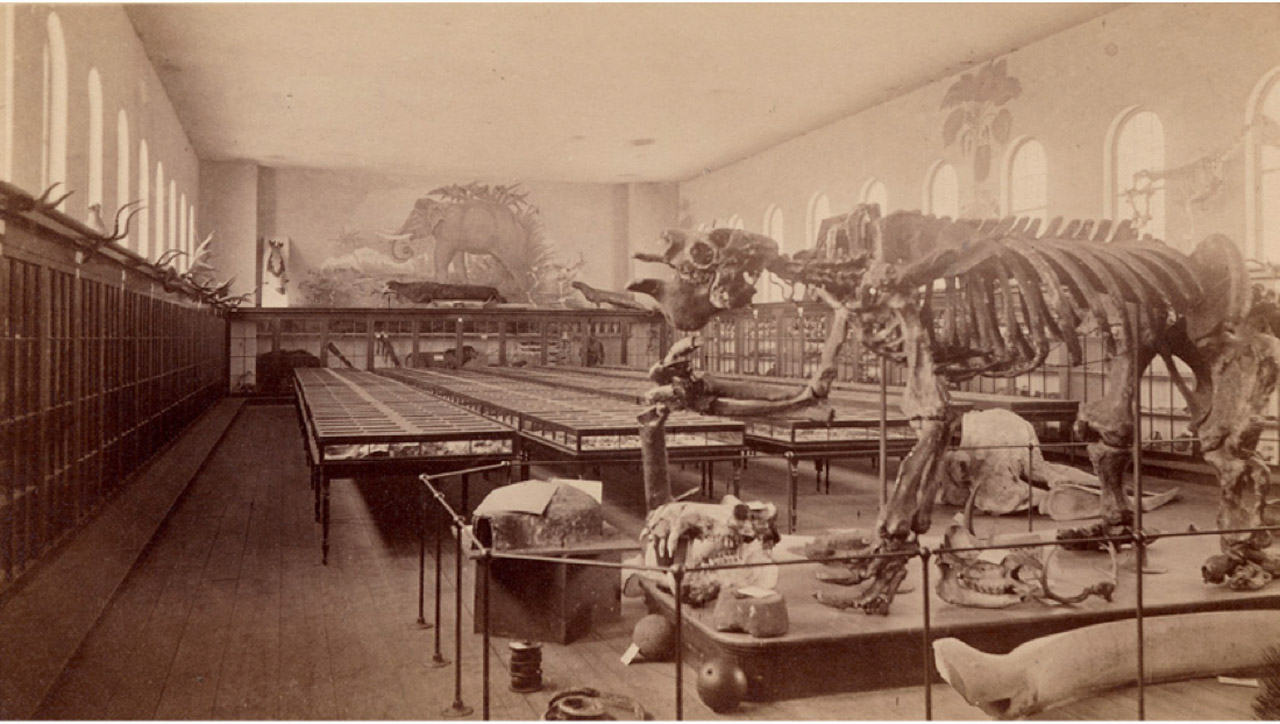

Amherst displays a cast skeleton of a Megatherium (giant ground sloth) in its natural history museum in Appleton Hall. (Amherst College Archives & Special Collections)

As for academics, science courses have improved dramatically and Amherst now owns 100,000 natural history specimens, including the world’s largest collection of dinosaur tracks — assembled by Edward Hitchcock — and an outstanding collection of minerals. Only juniors and seniors can take electives, including astronomy, botany, Spanish and anatomy.

Author Nancy Pick ’83

Photo by Mandy Demuth

The College is obsessed with oratory, the art of public speaking. For a senior, there is no greater honor than being chosen Class Orator. The finest speakers of the day come to Amherst, including prominent minister Henry Ward Beecher, class of 1834, and abolitionist Wendell Phillips, who champions the rights of women and Native Americans.

This year sees a major push for Amherst to become coeducational. Two women apply, a Miss Frazier of Watertown, Conn., and a Miss Lidd of Lynn, Mass. Several members of the Board of Trustees argue in favor. One is Beecher, who states: “Amherst is for universal education. If a man be Black, and is fully prepared, or a woman, and is fully qualified, its doors will be open to them.”

That effort fails, however. “As yet we cannot announce the arrival of any female Freshmen,” states the 1871 Olio, “nevertheless the time may not be far distant.” That prediction turns out to be overly optimistic: the first women won’t graduate until 1975, a century later.