In Memoriam: Calvin H. Plimpton ’39

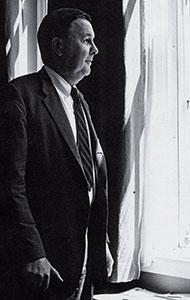

Plimpton in 1986, while president of the American University of Beirut. |

“I f you are crazy enough to be a college president,” Calvin Plimpton ’39 once told The New York Times, “the time to be one was in the ’60s.” Plimpton, who served as president of Amherst during the tumultuous era from 1960 to 1971, and as president of the American University of Beirut in the war-torn years between 1984 and 1987, died Jan. 30 of complications after surgery. He was 88 and lived in Westwood, Mass.

Plimpton, a physician who specialized in metabolic diseases, was 41 when he became the 13th Amherst president, succeeding Charles Woolsey Cole ’27. Plimpton came from a family long associated with the college: his father, George, Class of 1876, had been president of the board of trustees for 30 years; his brother, Francis, was in the Class of ’22.

During Plimpton’s tenure, the college increased enrollment, introduced a new curriculum and raised $21 million in a fundraising campaign. Plimpton also helped secure the initial funding to create Hampshire College. “He used a calm, fatherly approach to the academic and financial problems that confront all college presidents,” Time wrote in 1971. And when a medical need arose, according to Time, Plimpton would “pick up his black bag and make house calls around town.”

As Amherst president, Calvin Plimpton ’39, seen here in 1970, provided a steady hand during a period of student unrest. |

With poise, confidence and a self-deprecating humor, Plimpton led the college through other protests, including in 1970, when African-American students from Amherst, Mount Holyoke, Smith and the University of Massachusetts occupied buildings at the college for 14 hours, demanding increased black enrollment and control of a black studies program that the colleges had recently established.

The era was “about as wild a time as the college ever had,” recalls Hugh Hawkins, the Anson D. Morse Professor of History and American Studies, Emeritus. Plimpton “gracefully steered us through the storm,” says Kim Townsend, the Class of 1959 Professor of English, “or had the good grace to let others steer. Cal always had that half-smile on his face, as if things would be all right and we mustn’t get too frazzled. I think that temperament was just right.”

Plimpton attended Phillips Exeter Academy and Harvard Medical School. He served in central Europe with the 5th Auxiliary Surgical Group during World War II, then returned to Harvard and received a master of science in biochemistry in 1947. He became an assistant dean at the Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons, where also received a doctorate in medical science. He then chaired the department of medicine at the American University of Beirut.

As Amherst president, Plimpton saw three major buildings open on campus: Arms Music Center, Merrill Science Center and Robert Frost Library. President John F. Kennedy spoke at the groundbreaking of Frost Library in October 1963, in one of his last public appearances. At the event, Plimpton told the large crowd that they were present at “the birth of a memory.” The remark became poignant four weeks later, when Kennedy was killed.

After his time at Amherst, Plimpton was president of Downstate Medical School in New York City until 1978 and a professor of medicine at Downstate until 1983. He then spent a year working in international affairs at the National Library of Medicine. (John William Ward succeeded him as Amherst president.)

In 1984, Plimpton was serving as chairman of the board of the American University of Beirut when university president Malcolm Kerr was assassinated outside his campus office. Plimpton agreed to take over as president. His three years in the position were marked by escalating insecurity and the kidnapping of professors and other Americans. In an attempt to bring stability to the situation, he met with Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat in Amman, Jordan. Plimpton, always looking to interject a bit of humor, asked Arafat if there were any thoughts of kidnapping him. Arafat replied with a grin, “No, college presidents don’t command any ransom.”

While in Lebanon, Plimpton traveled with armed bodyguards. In 1985, a last-minute schedule change kept him out of a limousine that was stopped after leaving the Beirut airport. The passenger, Thomas Sutherland, dean of the university’s school of agriculture, was kidnapped by members of the group Islamic Jihad and held for more than six years. Plimpton was thought to have been the intended target of the kidnapping.

Plimpton served as a trustee of the World Peace Foundation, the University of Massachusetts, Phillips Exeter Academy, Long Island University and New York Law School. He was also a director of the Commonwealth Fund and an overseer of Harvard.

Plimpton is survived by his wife, Ruth; three sons, David, Tom and Edward; a daughter, Polly; and seven grandchildren. A memorial service will be held on campus in Johnson Chapel at 11:30 a.m. on Saturday, May 12. All are invited.

Photos: Top, Frank Ward; bottom left: Rawdon