Coach Thurston’s Playbook

By Kevin Graber

"I'm on the wrong side of 70," Bill Thurston says, "but I don't feel it." |

Theirs was a typical small New England dairy farm—12, maybe 15 head of cattle, a few acres of corn and string beans, an old pickup truck and some horses for plowing. As a boy, Bill Thurston milked cows, picked beans and hoed corn alongside his father, Chester, whose ancestors had migrated from England in 1635. At the end of each day, with the horses fed and the last fence post dug, father and son would stand and survey their patch of post-World War II Americana.

That Bill Thurston would emerge as one of the most influential figures in contemporary baseball history seems unlikely, if not extraordinary. But this farm boy from Norway, Maine, has done more than just guide the Amherst baseball team to more than 780 victories over more than four decades (good for 14th all-time, according to the NCAA record book). Thurston has directly affected the way the game is played, taught, staffed, researched, officiated and equipped at both the national and global levels—in a way that sets him apart from nearly anyone else since the demise of the flannel uniform. Thurston, now in his 43rd season at Amherst (while I’m in my third as one of his assistant coaches) is more than just a small-college baseball coach with a cache of wins. He’s a pioneering clinician, author, biomechanist, rules aficionado, safety advocate and international baseball ambassador, his fingerprints affixed on nearly every facet of the modern game, from rules to bat manufacturing to pitching mechanics.

As a boy, Thurston spent his idle hours peppering makeshift targets with rocks, snowballs and crabapples—whatever he could get his hands on. When that wasn’t enough, he batted beat-up balls off a homemade tee in the barn and recruited pals to help construct a backstop, home plate and pitcher’s mound on his parents’ cow pasture.

“If we didn’t take 200 swings a day, it must’ve been raining,” he says.

He played his first organized game at 13 and went on to star in baseball, basketball and football at tiny Norway High. By his senior year, he had sprouted to 6 feet, 2 inches and was already playing in a college summer league. He secured a baseball scholarship at the University of Michigan, where he batted .476 in conference play as a junior, nearly leading the Big 10 in hitting and emerging as one of the Wolverines’ top pitchers. He signed with the Detroit Tigers as a gap-hitting outfielder in 1956, spending the next several years in remote minor league outposts. But a future in Detroit never panned out. And so, with a master’s degree from Michigan in administration of physical education and athletics, Thurston taught and coached in Michigan public schools until he heard that Amherst was seeking a baseball coach. For his interview at the college, Thurston brought along a self-authored 50-page playbook to impress upon then-president Calvin Plimpton ’39 that he was a true scholar of the game. Thus began a coaching tenure that would outlast The Beatles, disco, the Cold War and the turn of a millennium.

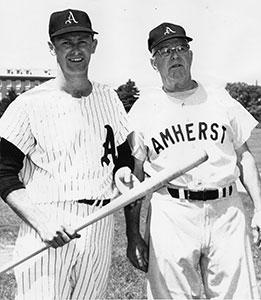

Thurston, left, was a young man when he replaced Paul Eckley, right, as Amherst baseball coach. |

Thurston replaced Paul Eckley, who coached 29 seasons at Amherst. Eckley, whom The Amherst Student called “the dean of American baseball coaches,” was one of the first inductees into the American Baseball Coaches Association Hall of Fame. But his program had fallen on lean times, with wins hard to come by. “Paul was a grand old man of baseball, and we loved him,” says Dave Martula ’66, who played three seasons under Eckley and one under Thurston. “But he was old-style, a grandfather. Then here comes this new guy who’s slim, trim and athletic, who knows his stuff, can play better ball than we can. I think he developed a competitive edge in all of us.”

The 1966 season, Thurston’s first, brought a 6-8 record. His first four clubs combined for a disappointing 34-53-3 mark. “It was tough,” Thurston says. “I’m not known for my patience.”

By 1970, with a trio of recruiting classes under Thurston’s belt, the program had begun to turn the corner. Out of high school, Dave Cichon ’70 had his pick of Division I schools but chose Amherst. Barry Roderick ’71, a future pro player, followed suit, as did Bobby Jones ’71 and Rich Bedard ’71, both future professional draft picks. By 1980, the Jeffs were churning out ECAC championships with regularity. The 1980 team boasted no fewer than nine players who ended up in professional baseball, including future major leaguers Rich Thompson ’80 and John Cerutti ’82. In all, 23 of Thurston’s players have signed professional contracts; at least 16 others work in administrative capacities throughout Major League Baseball.

Thurston can be a bear to play for, as he readily admits. “He pushed you harder than you thought you could be pushed,” recalls Neal Huntington ’91, general manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates (see “The personal touch,” page 36). “But he brought more out of me than I knew I had in there.” And victories have piled high. The Jeffs have cracked the 20-win plateau 19 times since 1973, securing five ECAC titles, a pair of NESCAC crowns and six NCAA Tournament berths. Thurston has earned four New England Coach of the Year honors.

As his reputation grew, Thurston spread his baseball gospel. Over summers and sabbaticals, he managed in the Cape Cod League, guided a professional club in Holland and coached teams for the Quebec Baseball Federation. He spent two seasons as head coach of the Australian National Team and one as pitching coach for the U.S. National Team. In the 1980s, he began dabbling in biomechanical analysis of the pitching motion and caught the attention of surgeon James Andrews, a founding member of the American Sports Medicine Institute. As a consultant for ASMI, a role he continues to fill today, Thurston observes surgeries and educates the medical community on mechanical flaws in the throwing motion.

“I’ve known many college baseball coaches in my career, and I’ve never seen one more involved in the prevention of injuries or more skilled at baseball biomechanics,” says Andrews. “Coach Thurston was one of the keys in bridging the knowledge gap between physicians, biomechanists and coaches.”

A tool Thurston uses to demonstrate the rotation of certain kinds of pitches. |

Thurston’s most recent instructional video, Common Mechanical Pitching Faults: Techniques and Drills to Teach Proper Mechanics, is a mainstay in coaching circles. He’s video-analyzed the mechanics of more than 1,200 pitchers, from Little Leaguers to Major Leaguers. “Coaches flock to him,” says Jack Hawkins, who runs a coaches’ clinic in New Jersey.

But Thurston’s career hasn’t been without controversy. In 1985, the NCAA appointed him to the prominent position of baseball rules editor, and for the next 14 years, he served as the organization’s official rules interpreter, recording suggestions for rules changes and ensuring technical accuracy of the rules. He fielded phone calls on trivialities such as balk calls and infield fly rules, often as late as 2 a.m., when games on the West Coast typically end. But when a growing concern about the safety of metal bats began to emerge in the early 1990s, his attention shifted.

As technology improved, metal bats became lighter and more powerful, sending offensive statistics soaring. Thurston and many others came to believe that the lighter bats compromised the integrity of the college game and increased the risk of injury to opposing players. After watching video of defenseless pitchers being drilled by line drives, often with gruesome results, Thurston pushed for legislation to temper the bats. The NCAA responded by shrinking maximum allowable barrel diameter by a fraction of an inch while also decreasing the differential between a bat’s length and weight. (Under the new rules, for example, a 33-inch bat can weigh no fewer than 30 ounces). In 2000, the NCAA disallowed bats exhibiting batted-ball exit speeds in excess of 97 miles per hour—but for a bat to be classified as illegal, three of the same model had to fall short in laboratory tests. As Thurston sees it, the NCAA got around its own rules by halting individual tests prematurely, before a bat even had the chance to fail three times. As a result, Thurston believes, bats that should have been banned were kept in circulation.

Disillusioned by the testing and by prominent coaches who received payment for endorsing metal bats, Thurston resigned as rules editor in 2000. In 1997, Thurston launched a six-year study, published in The Baseball Research Journal in December 2003, analyzing bat performance in the Cape Cod League. The results were arresting. Among 94 Division I hitters who met the study’s specific criteria, batting averages dropped .091 points when players used wood rather than aluminum, while home runs decreased by 61 percent and slugging percentages plummeted a whopping .190 points.

Thurston emerged as a leading authority on metal bats, which most NCAA conferences, including the NESCAC, continue to use. Thanks to recent legislation, today’s aluminum bats are safer than they were before, but Thurston and others continue to believe they pose a risk. Thurston has testified in trials against bat manufacturers, and he’s exhausted hundreds of hours reading case files and tracking data.

Seated behind an old wooden desk in his office at Amherst, Thurston takes out a hand-drawn tree that traces the progress of former players who’ve gone on to administrative careers in Major League Baseball: among them—in addition to Huntington—are Dave Jauss ’80, bench coach for the Baltimore Orioles; Dan Duquette ’80, former general manager of the Boston Red Sox; John Couture ’92, sports psychologist for the Cleveland Indians; and Ben Cherington ’96, Red Sox vice president of player personnel. Perhaps this is Thurston’s greatest legacy—former players, now at the game’s highest level, are spreading the lessons they learned from him.

“The basics haven’t changed for 150 years,” Jauss says, “and we all learned them because of him.”

On the field, Amherst’s team won NESCAC crowns in 2004 and 2005. After qualifying for the conference tournament again in 2007—the Jeffs were eliminated with a 6-3 loss to Williams—the team is now riding a streak of three straight 20-win seasons.

Teaching remains at the core of Thurston’s philosophy. “He takes the game apart and allows young players to see the way in which it should be played, and there’s a parallel between that and what academic faculty do in the classrooms with a book or a painting,” says Austin Sarat, the William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Jurisprudence and Political Science and faculty liaison to the baseball team.

At 73, still barrel-chested and perpetually tan, Thurston pitches batting practice almost daily. The playbook he once showed to Plimpton has expanded to two full volumes. “I’m on the wrong side of 70, but I don’t feel it,” he says. “I am still learning about the game. I’m still at the point where I’m asking why things happen and trying to figure them out. There are so many positives in being around these players, and hopefully it keeps me young.”

Graber, who played and managed in the minor leagues, is a former sports information director at Amherst. He now works as a residence director at UMass Amherst while he completes his master’s degree in education.

Photos by Frank Ward or courtesy of Bill Thurston