Reviews

Two Tonics for Teutonic Turpitude

- Cities, Sin, and Social Reform in Imperial Germany, by Andrew Lees ’62

- Infinite Variety: Exploring the Folger Shakespeare Library, edited by Esther Ferington

See also: Amherst College Books and What They Are Reading

Cities, Sin, and Social Reform in Imperial Germany

By Andrew Lees ’62

Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002. 424 pp. $65.00 hardcover

Those who buy this book thinking that it will be the Kaiser’s version of Sex and the City will be disappointed; but others will be rewarded by its discussion of a diversity of themes that are, perhaps surprisingly, very much relevant to political issues in America today. To be sure, the work is aimed primarily at historians of modern Germany, and it is framed by one of the major debates that they have conducted over the past 30 years. One influential school argues that Imperial Germany (1871-1918) was ruled by aristocratic and ultraconservative elites to whom the middle classes more or less willingly deferred; in this scenario, liberal and democratic values were muted, and Germany was started on a “special path” (different from that of other Western European countries) that culminated in the Third Reich. Another, equally vocal group of historians contends that, on the contrary, the middle classes of the Imperial era were very active and influential; but to see their efforts, one has to look below the level of national politics and examine events at the state and especially municipal levels. That is all the more important due to the fact that Germany, like the United States, had a federalist constitution in which major powers and responsibilities devolved upon the states and cities.

Andrew Lees, who specializes in both German history and the urban history of Europe and the United States, explicitly sides with the latter group of historians, and he makes a major contribution to the debate. If I were writing this review for a historical journal, I would assess that aspect of his book in much more detail. However, since only a few (though not an insignificant number of) Amherst graduates belong to the historical profession, I will highlight another side of the book, namely its relevance to ongoing debates, on this side of the Atlantic, concerning the nature of urban life, the “acceptable” latitudes of individual behavior and the relative responsibility of individuals, communities and the state for ameliorating social conditions and improving the moral fabric of the nation.

The similarities between German and American debates over the moral turpitude of urban life date back to the 19th century; indeed, Lees explicitly notes that he was inspired to write his book by Paul Boyer’s Urban Masses and Moral Order in America, 1820-1920 (1978). In the latter part of the 19th century, German cities underwent a population explosion in the wake of rapid industrialization; Germany surpassed England’s industrial output, and hence ranked second, behind the United States. The problems that this created were grist for conservative mills, which churned out litanies of invective against the putative evils of urban life: not just drunkenness, theft, violent crime and prostitution, but also nonmarital sex in general, “trashy” and “smutty” literature, secularism and declining religious faith, and especially the Social Democratic Party, the (nominally) Marxist organization that gained a third of the votes in the national Reichstag elections of 1912. These developments were noted with alarm by liberals as well, but they proposed different diagnoses and remedies. In the process, Germany experienced what we now would call a “culture war,” whose arguments still resonate today.

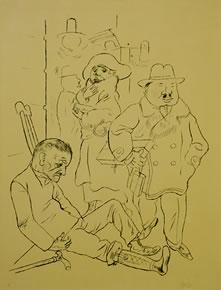

Conservatives focused on the individual moral failings of (primarily working-class) miscreants. This was reflected in a juridical mindset, dominant in the 19th century, which placed the blame for crimes squarely on the criminal, and meted out accordingly harsh punishments. Conservatives were equally appalled by those whose “deviant” or “immoral” behavior was not severe enough to be punishable by law; for such cases, they advocated a tougher penal code as well as heavy doses of moralizing. Though they held individuals ultimately responsible for their actions, conservatives contended that they were led astray, or encouraged in their deviance, by a variety of corrupting influences. High on that list were not only socialists and purveyors of literary “trash,” but also upscale authors who promoted secular and humanistic values: Henrik Ibsen, Emile Zola and above all Friedrich Nietzsche, who continues to be a bugaboo of today’s culture-warriors. But with a few exceptions, the conservatives were unsuccessful at passing harsher laws; and in the free market of ideas, they were singularly unpersuasive at improving the behavior of “immoral” urbanites. That was not surprising, given the fact that their moralizing tracts were replete with pompous sentiments and clunky sentences, like this one from 1890: “If a man wallows in the filth of impurity, his heart cannot rise to the ideals that ought to shine as the lodestars of our lives” (cited on p. 86).

Lees is much more interested in the liberal middle-class responses to urban crime, deviance and “sinfulness,” which he sees gaining importance and influence in the closing decades of Imperial Germany. Though hardly “soft on crime,” progressive liberals argued that criminality and deviance were produced not just by individual moral failings, but also by environmental factors like poverty, overcrowding and lack of “wholesome” leisure-time activities. They believed that government, at both the national and municipal levels, could play important roles in alleviating those problems; indeed, Imperial Germany was in many ways at the forefront of providing social insurance and city services. But at the same time, middle-class liberals were avid supporters of voluntary associations, which provided them with myriad opportunities for civic involvement. Lees singles out four individuals who mobilized middle-class volunteers to help the less fortunate. Volker Böhmert and Johannes Tews sought to improve leisure-time activities by founding Volksheime, establishments where workers could get low-cost (and low-alcohol) meals, as well as use reading rooms and attend educational lectures. Walther Classen was particularly concerned with improving the conditions of working-class youths, while Alice Salomon was especially successful at encouraging women to engage in social work, and she founded a school that gave them professional training in that area.

To be sure, there was nothing radical about these projects, whose origins in middle-class volunteerism might sound like “thousand-points-of-light” conservatism today. Though cognizant of environmental factors in causing deviance, the founders of those programs saw their major goal as the strengthening of self-reliance and self-discipline among the lower classes—a goal shared by 19th-century liberals and conservatives. But the liberals were distinguished by their unabashed enthusiasm for urban life. Unlike conservatives, who portrayed cities as cesspools of iniquity, or at best icy landscapes of social atomization, the liberals lauded cities as arenas of new opportunities, replete with diversity, energy and individual freedom. By tackling the undeniable problems caused by urbanization, middle-class liberals tried to improve their modern “home” in a nation where Heimat was usually coded as small-town, rural and engulfed in traditionalism. Though selfless charity was certainly part of their motivation, the urban bourgeoisie also had a vested interest in improving the lot of the lower classes, since it would contribute to the quality of life of the entire urban environment—and hence obviate the need to flee to the suburbs.

Lees concludes his book on a very optimistic note, by indicating the extent to which the conditions of the urban working class in Germany did indeed improve markedly in the years before World War I. If that was the case, then it was due to a recipe for social reform that combined government assistance with community volunteerism. Moreover, it recognized that the goal of making individuals self-reliant did not contradict, but was predicated upon, the insight that it could result only from a communal effort. Above all, it intuited that the viability of a city for all of its inhabitants was dependent upon the condition of its “lowliest” members. Those are issues that continue to confront city-dwellers—which most of us now are—today.

—Peter Jelavich ’75

Professor of History,

Johns Hopkins University

Infinite Variety: Exploring the Folger Shakespeare Library

Edited by Esther Ferington

Folger Shakespeare Library, April 2002. 222 pp. $60 hardcover

In the spring of his senior year, Henry Clay Folger (Class of 1879) attended a lecture at Amherst College given by Ralph Waldo Emerson. Folger was so impressed that he went on to read more by Emerson, including another speech in which Emerson said, “Genius is the consoler of our mortal condition, and Shakespeare taught us that the little world of the heart is vaster, deeper and richer than the spaces of astronomy.” Folger was so moved by these words that he made it his life’s mission “to collect in one place for posterity not only the works of Shakespeare but also the works upon which he drew or that alluded to him, and materials that conveyed the essence of his age.” The result was the establishment of the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., on April 23, 1932.

Infinite Variety is an impressive general description of the Folger Shakespeare Library, which is administered by the Trustees of Amherst College. It explains Henry Folger’s fascination with Shakespeare, his desire for a research library to house his book collection and his choice of a site on Capitol Hill, in Washington, D.C., where scholars would have easy access to its collections. It records the library’s evolution from a repository of Shakespeariana to a collection encompassing the English and Continental early modern age. It also documents the Folger Library’s ties with Amherst through the Amherst Board of Trustees, who continue to have responsibility for it. Most important, however, Infinite Variety describes some of its incomparable treasures.

The Folger Library owns the largest Shakespeare collection in the world. The collection, established by Henry and Emily Folger in the late 1800s, includes 79 of the extant 240 First Folios. (These are large volumes of Shakespeare’s collected works, published two years after his death. The First Folio, as it was later called, contained 36 of Shakespeare’s plays, 18 of which had never before been printed and would otherwise have been lost.) In addition, the library owns 200 quartos (small editions of the individual plays published in the late 1500s and the early 1600s), as well as books about Shakespeare, playbills, costumes, promptbooks, films and portraits. The text advises us, “Only two existing images are considered authentic likenesses of William Shakespeare: the memorial bust at Stratford and the engraving by Martin Droeshout for the ‘Vincent’ First Folio.” This volume, however, provides a generous sampling of the specious portraits and explanations of how they were misattributed.

The Folger Shakespeare Library’s holdings range well beyond works by or about Shakespeare. For example, Elizabeth I’s own copy of the Bishop’s Bible; the Caxton edition of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, 1477 (one of just 10 known copies); Henry VIII’s copy of Cicero inscribed, “Thys Boke is Myne Prynce Henry”; and the 1494 Thomas à Kempis text bound in blind-tooled pigskin and equipped with an iron chain.

As a member of the Amherst Glee Club and the College Choir, Henry Folger developed an appreciation for music that led him to collect early modern music, including the compositions of the English lutanist John Dowland, who received an appointment to the court of King James I in 1612. The handsome Harton lute from that period is pictured as an example of the musical instruments in the Folger collection. Members of the Folger Consort have performed early modern music at the Folger Library since 1977. English scientific thought of the period is represented in the collection by such important works as Newton’s Philosophia Naturalis Principia Mathematica, 1687.

The book also describes how the Folger reaches out to the Washington community and the general public with contemporary poetry readings, lectures, concerts, exhibitions and programs for children. The recently dedicated Wyatt R. ’61 and Susan N. Haskell Center for Education and Public Programs, located across the street from the main building, facilitates this part of the Folger’s program.

Editor Esther Ferington, Folger Librarian Richard Kuhta, Head of Reference Dr. Georgianna Ziegler, and Head of Photography Julie Ainsworth have all contributed to an attractive and highly successful book on one of the world’s great libraries. Infinite Variety is a book that is well worth reading and treasuring.

—Willis Bridegam

Librarian of the College