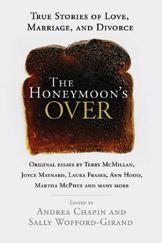

The Honeymoon’s Over: True Stories of Love, Marriage and Divorce

|

Edited by Andrea Chapin ’82 and Sally Wofford-Girand.

New York City: Warner Books, 2007. 368 pp. $24.99 hardcover.

Reviewed by Catherine Newman ’90

Last fall, for my 38th birthday, my husband, Michael, gave me a food mill—one of those hand-cranked gadgets for pureeing cooked fruits and vegetables. And for some reason, I’m thinking of this now after finishing The Honeymoon’s Over, the stirringly candid anthology of 22 essays edited by Andrea Chapin ’82 and Sally Wofford-Girand.

Chapin and Wofford-Girand cite that grimly familiar matrimonial fraction—“one of every two marriages ends in divorce”—but this collection of memoirs succeeds in transforming it from an abstracted statistic to a larger-than-life walk-through exhibit. It may be a cliché to describe personal essays as “honest,” but these are almost breathtakingly so. From Joyce Maynard’s “The Stories We Tell,” which struggles to understand the way narrative shapes our experiences (“My husband fell in love with our babysitter” turns out to be only part of the story of her divorce) to Ann Hood describing the agonizing triumph of her marriage after her young daughter’s death, these are essays that study relationships from every possible angle: illness, infidelity, abuse, addiction and suicide (and even, in Daniela Kuper’s fantastic second-person “Thursday,” the day her Sufi guru ex kidnapped their son)—and also forgiveness, comfort, delight, commitment and, above all, passion’s rise and fall. The book is edited with a light touch—too light in places, perhaps, in the case of Terry McMillan’s bizarrely itemized talk-show-style rant about her husband’s affair with a man—but the editors are like sympathetic listeners, capping the red pen while their writers ramble through their painful, revealing and even contradictory stories.

And what you begin to notice is that the marriages that work often have uncannily much in common with those that don’t—kindness, unkindness, job stress, beloved children. As you read, you rack your brain for the first line from Anna Karenina, even though it was on the syllabus of approximately 100 percent of your Amherst classes: Was it happy or unhappy families that are all alike? Happy, according to Tolstoy. But Chapin and Wofford-Girand assert something slightly different: “It may be easier to write about a marriage gone wrong than to divulge the inner workings of one kept afloat.”

Alice Randall says something similar in her poetic “What Happens in Vegas, Stays in Vegas”: “No one knows much about what goes on in someone else’s good marriage. Bad marriages are an altogether different beast.” And she should know. Married twice, Randall describes both the bad (“a long swim in an alligator pond”) and the good (“It’s a haven. It’s a pleasure box. It’s a sanctuary.”). The difference is in the details: she describes her second husband spooning cough medicine into her mouth in the night, writing, “I do not take the small kindnesses for granted.”

If the elusive goodness of good marriages can be captured at all, it may be this way: in the small kindnesses. In Elissa Minor Rust’s “Shifting the Midline,” for example, after her father’s brain tumor catapults her into a crisis of faith, Rust leaves the Mormon church that has been the foundation of her marriage. It’s her still-Mormon husband’s heartbreakingly simple gift to her that shows us what devotion looks like: a pair of regular underwear. Ann Hood’s husband demonstrates his commitment, even in grief, with a handmade anniversary gift every year: their wedding photo transferred onto cotton, glass or whatever the year’s designated material, “both of us looking younger as time passes, our faces free of the pain and loss waiting for us just up ahead.” In contrast, Zelda Lockhart describes a doomed-to-be-ex lover who “brought me flowers, having no idea that I despised the practice of cultivating something for the purpose of cutting it off.” (And, in an altogether different style of generosity, Patricia McCormick, on a break from her marriage, gives herself a stimulating gift that she calls, comically, “the electric husband.”)

I’m not saying everything boils down to good and bad presents, marriage just one big “Gift of the Magi” every second. This is the kind of anthology that keeps you turning pages, though, wondering about your own relationship. Where is the tipping point, when a good marriage turns bad, a bad one impossible to salvage? I kept reading lines aloud to Michael: “Are we like that? Like that?” Which is why I’m thinking about my birthday present now. A food mill is not a Pablo Neruda poem written across the sky in jet trails. But it’s exactly what I wanted. And when I grind steaming russets and sit down with my family to eat mashed potatoes in the twilight, I could not be happier. As Lee Montgomery puts it in “A Love Story,” “this love is embedded in the smallest and simplest of things.”

Newman, academic department coordinator for the college’s Creative Writing Center, is the author of Waiting for Birdy: A Year of Frantic Tedium, Neurotic Angst and the Wild Magic of Raising a Family. She writes the Dalai Mama blog.